Child

Soldier

Children’s

Advocate

Child

Soldier

Children’s

Advocate

Child

Soldier

Children’s

Advocate

ohamed Sidibay ’21 still remembers the first time he took a hot shower. He remembers the first time he had a bed to himself. And he will never forget the first time he ate at an all-you-can eat school cafeteria in his adoptive home of Maplewood, New Jersey.

“I filled my plate with enough rice to feed an entire continent,” Sidibay recalls. “I felt like I was eating not just for that moment, but for the time since I was 5 years old and for the rest of life that awaited me. My objective was to eat for the past, the present, and the future in that one sitting.”

There is a reason Sidibay remembers all these firsts, which most 28-year-olds would take for granted: Until the age of 14, his days were characterized by uncertainty over where he would sleep, if and what he would eat, if he would receive a quality education, and, most important, whether he would live

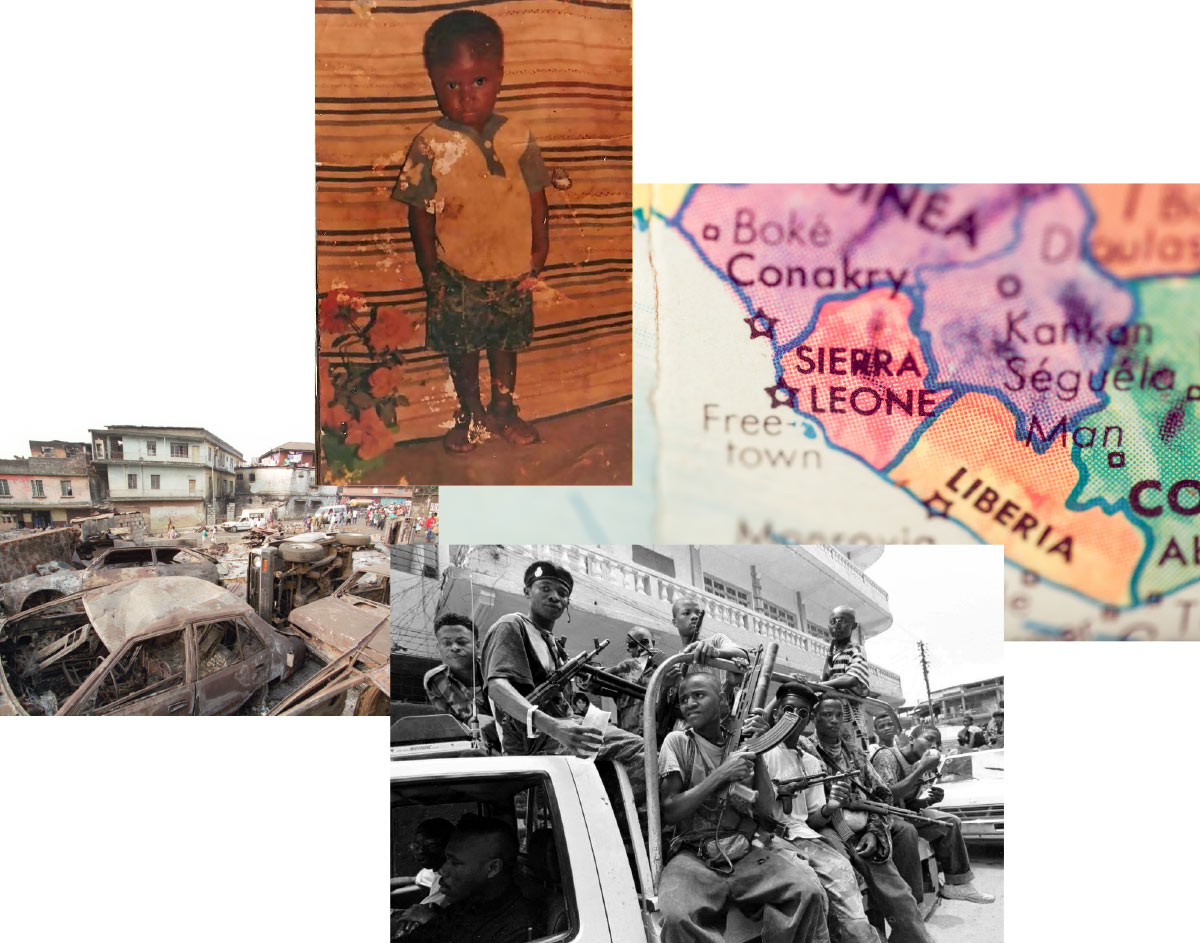

Growing up in Freetown in the midst of Sierra Leone’s brutal 11-year civil war, Sidibay spent the first half of his life trying to make himself smaller, if not invisible. “I assumed that if someone saw or noticed you, something bad was going to happen.”

That was a realistic assumption. When Sidibay was just 5 years old, he watched as rebel forces murdered his parents and siblings and burned his entire village to the ground. He was captured and forced to operate as a child soldier with the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) for four and a half years.

“For months after that, I kept trying to figure out how I could get home,” says Sidibay. “I didn’t realize that the home I wanted to get to no longer existed.”

He slept wherever he could: in the middle of the bush, on crates in the village the RUF had just ransacked, places where there was life before they arrived. “I traveled my country in a way that no one should ever get to know their country, because everywhere they took us, we left behind evidence of destruction and murder and rape,” says Sidibay. “I saw the evil that humankind is capable of.”

Sidibay’s life was characterized by uncertainty and despair, and above all, a lack of hope. He felt there were no options, nowhere to escape to. He knew he could die at any moment, and he accepted that. “It was better than the life I was living,” Sidibay says.

As an activist and a survivor, Sidibay is not deterred by these numbers. “I’m constantly striving to see how far I can push the boundaries and to challenge the way things have been done before when it comes to providing education to children who need it the most,” he says.

“I’m terribly proud of how well he’s done so far,” says Helen Bender, Sidibay’s Contracts professor, who helped him discover that he wants to work in private law related to project finance and general mergers and acquisition. “He’s a wonderful person, and I can’t believe how cheerful he’s been after all he’s been through.”

Clearly, much of his motivation for his activism comes from his own experience, as Sidibay was once one of these children. “The fact that I received quality education has been my opportunity,” he says. “It’s allowed me to dream beyond my imagination.”

After his release, Sidibay was enrolled in the Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration of child soldiers (DDR) program, sponsored by the government and the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone. Sarah Beeching is the founder of Oshun Partnership and a development consultant for the U.N., the World Bank, and, a range of other organizations. She worked in Sierra Leone for the U.K. in the late 1990s, helping to build the DDR program, and as a member of the peace negotiation team. She first met Sidibay at the U.N. headquarters in New York in 2017. “He stopped me in my tracks,” she says, describing her first interaction with Sidibay at the U.N. in 2017 when he approached her after a high-level meeting on education. “In a few short words, we established a connection. Until that moment, I had never encountered a child who had gone through the DDR program and come out the other side. Most people who face that kind of tragedy don’t ever overcome it.”

UNICEF became aware of Sidibay through the DDR program and began the uphill battle of enrolling him in school. He was 10 years old the first time he stepped into a classroom. The education he received was basic: He learned how to spell his name and how to count. There were no books to read. “I didn’t appreciate the importance of education back then,” says Sidibay, “because there was nothing to appreciate.” He attended school because it was the safest place for him to be, a block of time during the day that he could be somewhere with a roof.

Still, Sidibay longed for a better life, one with certainty and stability. And as he looked around at the lives of others in Freetown, it became increasingly clear to him that education was the path to achieving these things. At the time, he imagined growing up to be either a priest, a doctor, or a lawyer. He didn’t know much about what any of them actually did, only that they helped people, they had food, and above all, they were educated. “The value of education came not from what I was going to do with it, but from the knowledge that I wasn’t going to wake up and wonder where I was going to get a meal for that day,” Sidibay says. “And that pushed me to appreciate the power of education.”

Doing so turned out to be a decision that changed Sidibay’s life. He was brought to the U.S. by the organization, accompanied by the head of iEARN-Sierra Leone, Andrew Greene, in order to speak at a conference on the campus of Kenyon College in Ohio about children caught in the crosshairs of war. At the time, college was still a pipe dream for Sidibay, and it was during that visit to Kenyon that Sidibay fully grasped the power and possibilities of education. “It was the first time I heard people engaging in intellectual debate about books I’d never read, places I’d never been to, ideas that I quite honestly couldn’t conceive, and it made me realize I wanted to go to college.”

The trip was initially intended to be just five days. When it was time to return home, Sidibay intentionally skipped his flight out of JFK Airport. “I would go back to Sierra Leone, and life would go back to what it was: a life of uncertainty and not knowing where I was going to sleep,” he recalls. Telling his chaperone that he was going to use the bathroom, he slipped his passport into his back pocket and walked right out of the airport. He had no plan or any idea where to go.

Sidibay spent the next four months in homeless shelters, moving from shelter to shelter in New York, Rhode Island, Delaware, and Pennsylvania. “I found myself homeless in a country where I did not know homelessness existed,” says Sidibay. In the midst of all this, his visa had expired, leaving him undocumented. “It was a scary feeling,” he says, “because while Sierra Leone was tough, I adapted to the lifestyle that I had been living in the slums and on the streets. I knew the streets. I knew the slums. But in the U.S., I barely knew the language or culture or people, nothing beyond what I’d seen on TV.”

After four months going from one shelter to another, Sidibay ran out of options. Worn down by his situation and desperate to get out of perpetual homelessness, he called the only person he knew in the U.S.—a filmmaker named Austin Haeberle who had made a Peabody Award–winning documentary about child soldiers that past summer, which featured Sidibay. Haeberle came up with the idea for him to live with a family in Maplewood, New Jersey, whom he knew personally.

Living in an American suburb was a big shift for Sidibay, who was used to the chaos of cities. “What I didn’t realize back then was that I would’ve been completely screwed had I gone through the foster care system in New York City,” he says. “I didn’t have the education foundation to succeed, so I’m glad Austin knew enough to not let me go through that.”

It took several months for Sidibay to begin adjusting to his new life. For the first time ever, he had his own room with his own bed. “I felt like a stranger,” he says, though by now he thinks of his adoptive family as his family; he’s very close with them and visits often. “Back then, I still had this idea of making myself small. I didn’t want to be seen or noticed.”

Sidibay would also be starting his formal education as a 14-year-old at an American high school. He was constantly beset by self-doubt. “People told me after the war that I wasn’t going to amount to anything,” he says, “and that voice was still in my head. There are certain rooms that I find myself in and question whether I’m in that room because of my story, or if I’m invited into that room because of the work I do.”

Now that he no longer needed to worry about where he would sleep and what he would eat, Sidibay was able to place more focus on school. In addition to the quality education he received in high school, Sidibay strongly believes living in a home with stability is what enabled him to graduate. “I cannot sit here and tell you that I knew education was going to save me, because the reality is I wouldn’t have bet on myself 12 or 14 or 16 years ago,” he says. “It was only when I was told that I could do it, when going to college was expected, that I fully grasped the importance of education.”

Sidibay chose to attend George Washington University for his undergraduate studies, drawn by the Elliott School of International Affairs. He was increasingly interested in global policy, and the Elliott School had a number of professors who were practitioners working on policies in other countries, including Sierra Leone. Sidibay’s activism began to take shape throughout his college years as he became increasingly aware of his newfound privilege. “I was sitting at this institution with professors who are highly accomplished in their fields, debating theoretical topics,” he says. “And thinking, ‘There are thousands of children who went through the same experience that I went through, who cannot afford to have these debates about the world. If I don’t speak up for them, then what’s the use of the opportunity I’ve been given?’”

After graduating, Sidibay began working with the MyHero Project, a nonprofit that invites positive role models from around the world to share their stories, with the goal of empowering others to effect positive change. From there, UNICEF and UNESCO reached out to him. UNESCO became familiar with his work through various U.N. and Global Partnership for Education (GPE) events, which led to his current appointment as a member of the UNESCO High-Level Reflection Group on Strategic Transformation. By soliciting funding from the people he met through these organizations and others familiar with his story, he established a foundation in Sierra Leone that gives children, especially girls, educational opportunities. “I wanted to help the next generation of young Sierra Leoneans to have opportunities and access to quality education so they can compete with the rest of the world,” he says, “rather than be bystanders.” It operates as a social credit nonprofit, where the foundation will pay tuition fees in exchange for the students tutoring one another or helping their community as a way to pay back the organization.

Sidibay originally envisioned becoming an international human rights lawyer. He arrived at Fordham thinking that you could be either a public interest attorney or a private attorney, not knowing there could be cross-work between the two. It wasn’t until his first year that he realized this was possible, after he was invited to present at an event for the UNICEF International Council in Florence, Italy. There, he encountered people who were working in the private sector to finance projects run by UNICEF and other NGOs. “I realized then that you cannot separate the public and private sectors,” he says. “It’s a false dichotomy.”

Sidibay argues that in order for countries to develop proper infrastructure—including new roads, an independent judicial system, opportunities for foreign investment, and of course, a strong education system—they need private funding and investment. In order for UNICEF and UNESCO to continue to do the work they do, they need money. He points to development in Sierra Leone as an example. “Absent a private-public partnership,” says Sidibay, “the government in Sierra Leone simply doesn’t have the money or the power to stimulate the economy.” At the same time, this private investment must benefit the citizens of that country, which is where the public sector factors in. “People have to be employed from within that country, they must benefit from what’s being developed.” Working together, he believes, the expertise of each sector can produce an optimal outcome.

Sidibay credits his coursework and his teachers at Fordham with helping guide him toward the kind of law practice he would like to pursue. “A mix of professors have pushed me toward seeing the parallel between the public and private sector,” he says, “and that they’re not mutually exclusive.”

In addition to Contracts with Professor Bender, Sidibay says he benefited greatly from Corporations with Professor Caroline Gentile. “She’s an engaging, animated professor who made my second year a really wonderful experience,” he says. Professor Karen Greenberg’s National Security class also had a great impact on his views and allowed him to consider issues of national security from a legal perspective. “Listening to Professor Greenberg interview guest speakers made me realize that she’s guided by a moral compass that’s similar to mine,” says Sidibay. “There are things that are right and things that are wrong, and there’s no way to justify unlawful conduct by the U.S. government in the interest of national security.”

Johnson and Sidibay met at a Black Law Students Association event during their first year and have gotten to know each other through their study group since then. Johnson is from Mobile, Alabama, and has had a different lived experience than Sidibay as a Black man. “When we talk about legal issues and the future of the Black community globally,” says Johnson, “I can bring the perspective of African Americans, and Mohamed brings an international African perspective.” Recently, they stayed up late into the night on campus discussing the obligations and duties of Black lawyers in America. “Often we have different views,” says Johnson, “but we’re able to hear one another.”

Sidibay’s thoughts on these duties and obligations were put into practice as the Black Lives Matter movement took hold and protesters filled the streets of New York City following the killing of George Floyd. “Those were very depressing times for me and my friends,” says Sidibay, “as young Black men, in a country we love.”

Sidibay made a conscious decision to go to the protests on behalf of the Lawyers Guild with the role to observe and make sure that when people were arrested, their details were taken down and passed on to lawyers who could represent them. “While I went as a ‘neutral party,’ the main reason I decided to go is because I am a Black man in America,” says Sidibay. “We’re told every day that if we check all the boxes and do everything our society tells us to do, then we’ll be, in the words of James Baldwin, the exceptional negroes. But regardless of all of that, when we walk down the street, we don’t have a sign that says ‘a Black lawyer,’ ‘a Black nurse,’ or ‘a Black professional.’ We just have a sign that says we are Black. Even if we follow the law, we don’t get the benefit of the doubt most of the time. There are systems and institutions that we find ourselves in that haven’t been built for us.”

But for now, Sidibay plans to begin his law career in New York. After returning to the city for graduation in May, he looks forward to joining Covington & Burlington, LLC, as an associate this fall. “The mixture of big law and public interest is very important and personal to me,” he says. “So I’m excited about joining a firm where I don’t have to choose between working in the private sector and my advocacy work.”

During his final year at Fordham, Sidibay has remained actively involved with GPE, planning its Global Education Summit this summer with the goal of raising at least five billion dollars to support schools in partner countries. In February 2019, he served as a keynote speaker and co-host at the GPE’s second replenishment conference in Dakar, rubbing shoulders with numerous heads of states and prominent figures, including President Emmanuel Macron, Senegalese President Macky Sall, and musical artist Rihanna. Sidibay now hosts a virtual show once a month with changemakers from around the world, including ministers of development from different countries and the heads of U.N. agencies (he recently hosted Canada’s Minister of International Development Karina Gould and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi) in an effort to raise awareness and create buzz around the conference.

Alongside his career in law next year, Sidibay plans to continue to engage strategically with GPE, UNICEF, and UNESCO and explore board opportunities so that he remains actively engaged in that world. “I am aware that a corporate associate’s life will bring its own set of new challenges,” he says. “However, they will not deter me from my other goal of ensuring that the right to quality education is not determined by one’s place of birth, citizenship, social status, or sexual orientation.” He has taken a step back from his foundation work in Sierra Leone, as the government recently launched an initiative that provides free admission and tuition to all children in government-approved schools.

Sarah Beeching of Oshun Partnership has become a mentor to Sidibay, offering ideas on speaking engagements and activities that would make the best use of his time and talents without compromising his studies. “He is an incredible advocate for development and a great inspiration to me personally,” says Beeching. “He deserves every success in his law career and happiness in the future.”

Part of Sidibay’s motivation and persistence—both as a child and as an adult—stems from a desire to transcend expectations and define himself on his own terms. “Throughout my life, people have wanted to put me in a box,” he says. As a former child soldier who grew up in the slums, a certain degree of stereotype follows him everywhere. “If there is a box,” he says, “I will be the one to dictate the size and shape of it. I want my advocacy work to be viewed beyond the first half of my story.”

At times, Sidibay still finds himself in disbelief over how far he’s come, the life he has now, and the opportunities he’s been presented. “I fear that one day, I’ll wake up and find out that all of this was a dream,” he says. “That I’m still lying outside of someone’s porch in the slums of Freetown, hoping I’ll wake up before they do.”

And yet, rationally, he knows that no one can take away all that he’s achieved. He’s worked hard to be in the rooms he now finds himself in. And as he finishes up his final year at Fordham and embarks on his career and a promising future, he is focused on continuing to create opportunities to make change for children and discovering what else the world has in store for him.