Those Who Have Come Before

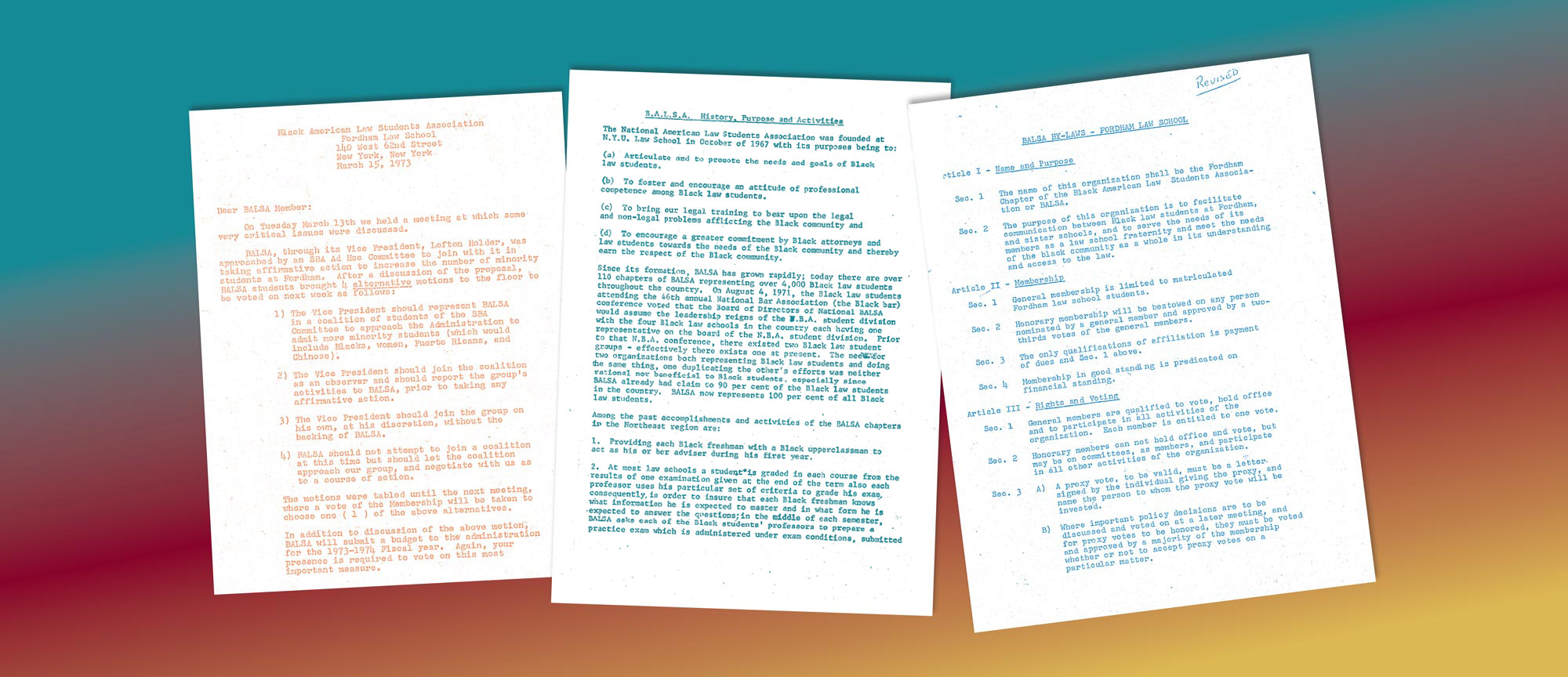

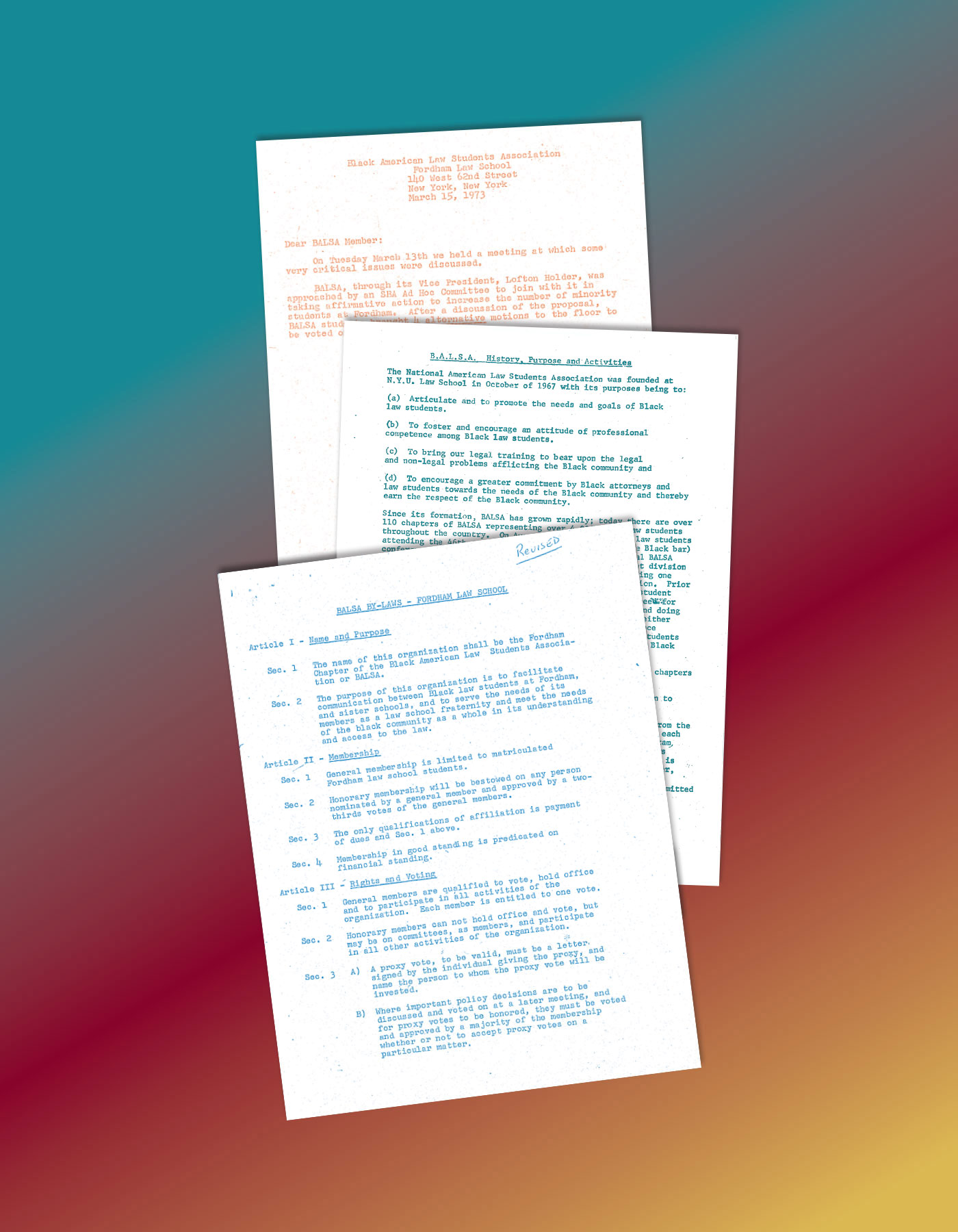

“I assumed it was an old photo album, but when I started looking through it, I saw that it contained the founding documents of Fordham Law’s BLSA,” she said.

Noticing the dates on the documents, she realized that the group’s 50th anniversary was approaching. “I couldn’t believe that we were totally unaware,” she said.

Owes immediately shared the news with Rian Morrissey ’24, BLSA’s chair of professional development, who was sitting nearby, then dialed Ferrell Littlejohn ’24, BLSA’s vice president, who was out to dinner with friends. “We were all floored,” said Littlejohn.

Celebration and Reflection

“The whole idea was to get Black students applying and admitted, since Fordham was behind NYU and Columbia Law in terms of numbers,” said Olivia Valentine ’74, who co-chaired BLSA in its second year, in 1973–1974. “We put out a huge effort, including inviting law school recruiters who interviewed Black undergraduates on the spot,” recalled Valentine, who spent 11 years as a city council member for Hawthorne, California, and was an attorney for the Federal Aviation Administration.

Littlejohn says the event brought Fordham Law’s current Increasing Diversity in Education and the Law (IDEAL) pipeline program to mind, but even more striking was an initiative to advocate for the hiring of Fordham Law’s first Black law professor, something that didn’t happen until more than a decade later when Judge Deborah A. Batts joined the faculty in 1984. (Judge Batts would go on to receive tenure in 1990. After her death in 2020, a scholarship was endowed in her memory that provides support for students dedicated to using their legal education to promote social justice, civil rights, and equality; Owes and Littlejohn are both recipients of the scholarship.)

“So many of the issues we’re focused on now, like getting more Black professors, are issues they focused on back then,” said Morrissey. “The same challenges they faced are the ones we are facing.”

A Numbers Gap

Judge Eugene Oliver ’77, who was co-chair of BLSA along with Valentine in the group’s early years, remembers very well what it was like to break new ground. As an evening student in Fordham Law, he had to redo several years because of his daytime workload at a community development agency focusing on anti-poverty programs. “It was also tough finding a job once you got out of law school—in fact, it was tough all along,” said Oliver. He would build on his experience co-chairing BLSA at Fordham by helping to start the Black Bar Association of Bronx County, and would later serve as a judge on the Bronx Supreme Court for 27 years. “I was mindful that, whatever I did, I would make a lasting impression on others in the field, so I made it my mission to talk to any new judge on the bench who was Black, as well as to help Black attorneys who aspired to be judges.”

Lofton Holder remembers reaching out to help the Black community through BLSA while at Fordham Law. “We set up a table in front of the state office building at 125th Street, put up a BLSA sign, and gave passersby advice on legal issues,” he recalled.

That was part of BLSA’s mission to help the Black community succeed, both outside the Law School and within. “There were a lot of things we wanted to do to help Black students at Fordham, including scholarships, tutoring programs, and mentoring them in everything they needed to know to move ahead,” Valentine recalled.

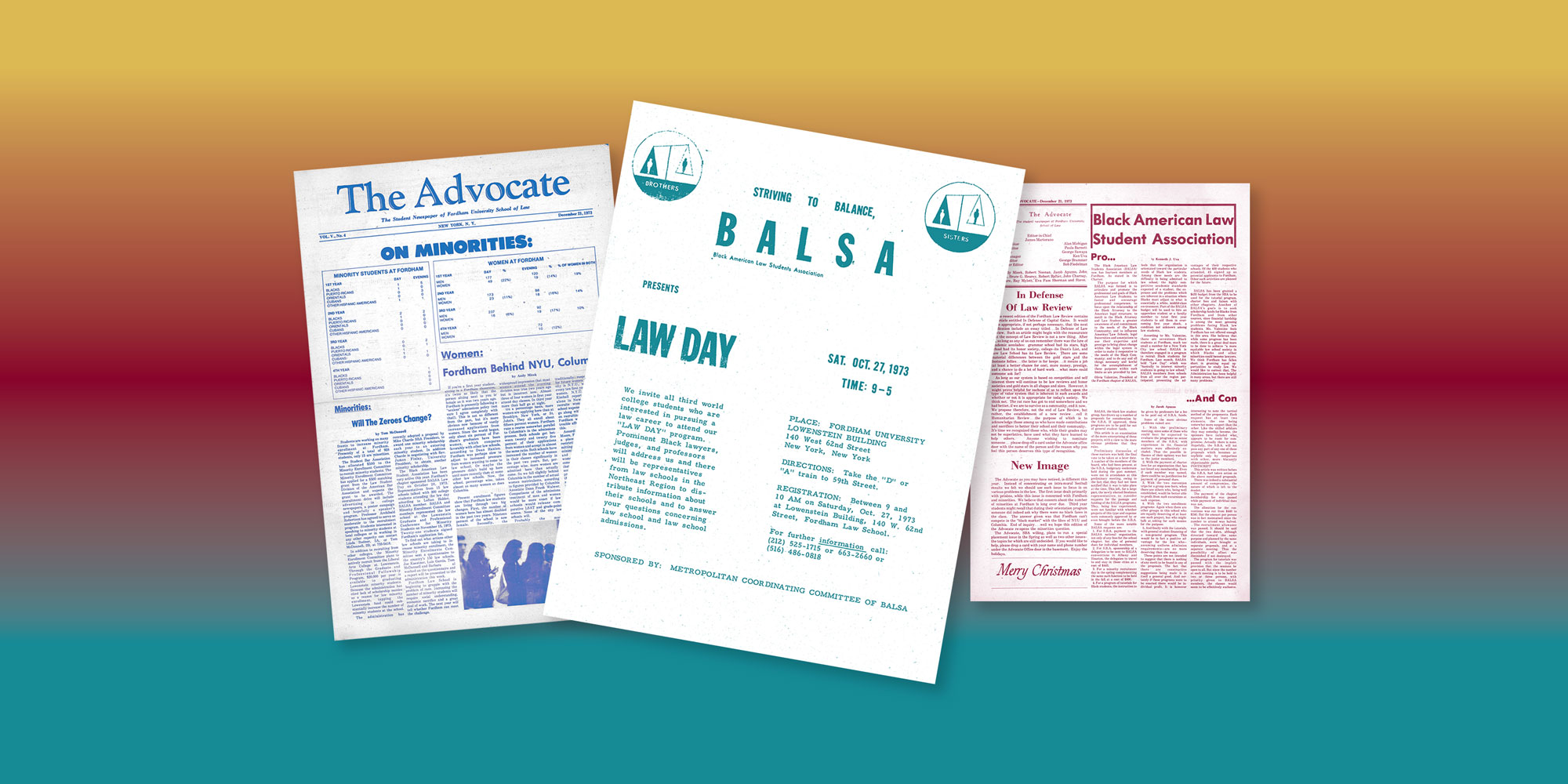

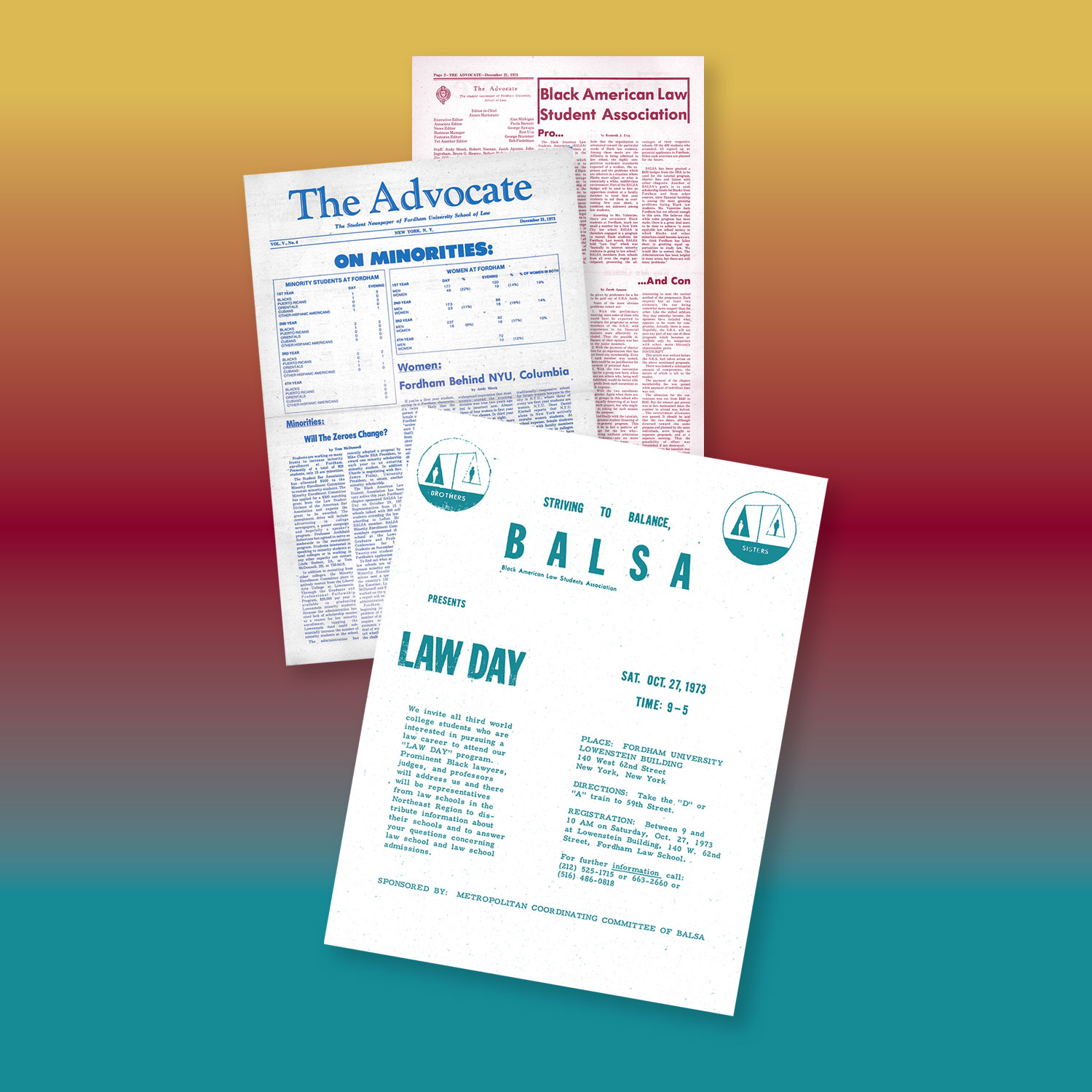

That budget battle was reflected in one document that Owes uncovered: a clipping from The Advocate, Fordham Law’s student-run newspaper, from December 21, 1973, which presented pro and con views of BLSA proposals for a budget increase to cover tutoring for Black law students, as well as trips to conventions; a minority recruitment program; events to bring speakers to the Law School, like international human rights attorney Professor Lennox Hinds, founder of the National Conference of Black Lawyers; and other expenditures. “Having people like Lennox Hinds come to campus motivated us, and it wasn’t something we could get from the student council,” said Holder. “Being in BLSA felt like preparing for the major leagues—we went to BLSA conferences in Boston, in Atlanta—it all made us more effective.”

In the Advocate article, the “con” writer framed BLSA’s request for funds, including those for tutoring, as “a positive advantage for the few who—assuming uniform admission requirement—are no more deserving than the many.” Valentine begs to differ. “The issue then—and now—is that public school education in Black neighborhoods is often substandard,” she said. “That’s why we don’t have large numbers of Black people in law school and in law.” That problem was the focus of the cover story in the same 1973 issue of The Advocate, which addressed the representation of minorities and women on campus. At the time, of 928 students enrolled at the Law School, 24 were people of color. Of those, 13 were Black, making up less than 2% of the student population.

Lack of representation was only one reason BLSA felt so necessary to Valentine, Oliver, and Holder. “Most of the Black students at Fordham at the time went at night—and many of them were cops,” said Holder. “I was a full-time day student, and, besides me, there was only one other Black man in my class.”

For Olivia Valentine, the experience at the Law School, including with BLSA, was, she said, “the genesis of all the success I had in my professional life—including the tough, brilliant professors I had, like my evidence professor Michael M. Martin. But we still knew that we needed more numbers, and we rolled up our sleeves to help solve the problem.”

Now, Owes, Littlejohn, and Morrissey want everyone at Fordham Law to know about BLSA’s 50th anniversary milestone and gain a deeper understanding of the experiences of Black students at Fordham Law over these past five decades.

“We want to show the progress in terms of how well students are doing, the connections that are being made, and the spaces we couldn’t enter that we can now,” said Morrissey.

One example of that progress: Fordham Law now has 13 Black professors on its full-time faculty. “Our BLSA predecessors were only 10 years out from the Civil Rights Movement,” said Morrissey. “There’s so much more we can do with our influence in 2022—and we have a responsibility to future generations.”

Yet significant disparities still exist, both in law schools across the country and within the legal profession itself. Legal education and the legal profession remain nearly as overwhelmingly white now as in 1972. Back then, 4% of all law students in the U.S. were Black. Now, Black law students make up 7.5% of law students in the country, according to the National Association for Law Placement (NALP). (Black Americans make up 14.2% of the total U.S. population, per the 2020 U.S. Census.)

“It’s not surprising to me that some of the issues haven’t changed,” said Morrissey. “In my first year at Fordham Law, I was the only Black man in my evening program class of 60 students. Enrolling more Black students, and providing them with as many resources as possible, continues to be a hurdle.”

An Investment in Community

Delving into the archives of BLSA also brought her late mother to mind. “My mom always taught me that history is important for understanding the context of everything we do,” she said. Like Owes, her mother was also a single parent in Harlem. (Owes has a 3-year-old son.) “My mother always wanted to be a lawyer,” Owes said. “Once, she found a set of law school textbooks out on the curb and was so excited to read them. When neighbors would get eviction notices on their door, she’d go to court and fight for them—and she’d win, which is really hard to do for a pro se litigant. She was the reason I wanted to go to law school.”

Now, Owes says she sees her tenure as BLSA’s president as a “calling,” a way of investing in a community that has already invested in her. “Being a 1L is so hard; it can take a toll on your self-esteem,” she said. “But BLSA made me feel like I belonged. It’s a genuine, authentic space in a world of secret handshakes. [In law school,] you have to know where to find resources, how to take an exam, how to write a certain way. If it weren’t for BLSA, I wouldn’t have gotten the grades I did or my summer jobs.”

Valentine also credits BLSA for the success she achieved despite the barriers she experienced as a Black woman in the field. “In my very first law job, as an intern in a Black law firm, the men were allowed to go to court, but I wasn’t,” she recalled. “I had to sit in the back and write motions and pleadings. But co-chairing BLSA taught me how to be a leader at a time when women weren’t being given those opportunities, and how to negotiate with strong-willed men who wanted to get their way.” Despite not being able to go to court, Valentine worked with the legal secretary at the firm to learn how to do filings and work in the court system. “I ended up learning it better than my male colleagues, because I started from the ground up,” she said.

For Littlejohn, what stands out among her experiences in BLSA is the advice and coaching she has received from fellow members, particularly when she was taking first-year Legal Writing. She credits BLSA member Tarique Zacharia ’23 for helping her get through the course. “He took me through the entire process, and I succeeded,” she said. “I’m now a TA for Legal Writing.”

Team Spirit

Today, significant inroads are being made on that front, partly due to the mentoring efforts of groups like BLSA. Last year, Tatiana Hyman ’22, who served as BLSA vice president in 2020–2021, became the first Black editor-in-chief of the Fordham Law Review. Abdulai Turay ’22, who served alongside Hyman as BLSA president, was named the 2021 Law Student of the Year by The National Jurist. But there’s still work to be done—and BLSA is doing it, whether holding exam workshops to help Black students succeed in their classes or pass the bar, or résumé workshops to help them get jobs after graduation. “That’s a big part of what we do,” said Owes, who cites sobering American Bar Association figures for 2021 showing that only 61% of Black students passed the bar on their first try, compared with 84% of white students.

Part of the reason for those disparities comes from the isolation many Black law students say they feel in law school, isolation that often continues after graduation, particularly in the top law firms. Some recent numbers from the 2021 NALP Report on Diversity illustrate the gap: Black lawyers made up only 5.22% of associates at top firms, and only 2.22% of partners, well behind other people of color. Black and Latinx women each represented less than 1% of all partners.

“You have to look at the data,” said Benson Martin ’00, the new chair of Fordham Law’s Alumni Attorneys of Color (AAC) affinity group. “There’s a small representation of Black students in law school and on Law Review, and that number only goes down when you look at some of the most desirable jobs, whether at big law firms or the Manhattan District Attorney’s office.”

Fifty years on, there’s still an urgent need for organizations like BLSA. “We need them in law school and after law school, whether studying for the bar, figuring out how to get on Law Review or Moot Court, or for help navigating on-campus recruiting,” said Brenda Gill ’95, deputy counsel at OneMarketData. Gill is first vice president of the Executive Committee of the FLAA and the founder of the AAC. “We’re all better off with everyone’s participation.”

Expanding the Network

For Morrissey, networking through the REAL Scholars program and BLSA opened the door to a multitude of opportunities. The REAL program is designed to help students from underrepresented communities succeed in their first year in law school. Through that program, Morrissey met BLSA’s previous president, Ryan Washington ’23, who, in their very first meeting, encouraged him to not only join BLSA but to become an officer.

“[Washington] was a great mentor to me,” said Morrissey. “He helped me figure out how to study and what everything meant; he even helped me get my summer job at the Queens District Attorney’s Office.” Those experiences bolstered his confidence and led him to take chances—like putting himself forward to be a class representative in the Student Bar Association.

When Littlejohn didn’t make the Dispute Resolution Team on her first attempt, another BLSA member, Shayonna Cato ’22, encouraged her to try out again. “Shayonna came up to me after the tryout and said, ‘You did a great job—even if you don’t get in this semester, go out for it in the summer,’” she said. “I did, and now Rian and I are both members of the team.”

That sense that someone is looking out for them can be particularly crucial for students of color, as well as for first-generation law students like Owes, Littlejohn, and Morrissey, who say they often feel a disconnect between the law school and their lived experience. “Sometimes, we’ll be talking about a case in class that has everything to do with race, but we discuss it in terms of the law, in a neutral way, and race isn’t mentioned,” said Littlejohn. “But to me—to us—we’re reading about racism, something that affects our everyday lives.”

Bridging the Gap in the Legal Profession

Alumni of color like Martin and Gill are also hoping to strengthen that student-alumni connection—and use it to help students while they are in law school and beyond. “Recently, we held a Zoom discussion geared to first-year students of color, with alumni offering advice on the ins and outs of law school and how to play the game,” said Martin. “It’s good for students to see successful people who look like them explaining how they approach things, and we want to continue to see what alums and students need, whether mentoring or networking. That’s our goal.”

The library team will also digitize the BLSA documents that Owes found last August and share them as part of its digital collections. “BLSA has a long history, but that history will stay hidden if the documents stay hidden in files that no one has seen,” said Todd Melnick, clinical associate professor and director of the law library. “Besides being a public service, making these documents available to everyone is right in the center of the library’s mission.” Added Littlejohn: “We love BLSA, and we’ve been carrying on for 50 years. But it’s not only about love; it’s about action, like working with the library to uncover the past and correct past wrongs, including giving back to our Black and brown students today.”

Meanwhile, Littlejohn said she appreciates her time at Fordham Law here and now. “Like Rian, I came in with the REAL Scholars program, so I had a built-in family, and that has continued,” she said. “I haven’t experienced that hypercompetitive atmosphere that you hear about with most law schools. The administration is so supportive, and it’s clear they are actively working on diversity, equity, and inclusion. It’s easy to find your group of people here who will stick with you no matter what.”

Added Morrissey, “Despite the systemic barriers in our society, we continue to make progress every day.”

Olivia Valentine agreed: “Absolutely—there is no comparison with the opportunities Black people are given today compared with when I came in.”

That’s why Owes and her fellow BLSA officers want the events they are putting together in the spring to be a celebration of the past and the promise of the future. “The 50th anniversary is an opportunity to tap into our alumni network and our students and help all of us feel proud and empowered,” said Owes. “Above all, we want it to highlight the efforts of the students who have come before us and continue to clear a path for those who come after us.”