His Own Write:

What John Lennon Taught Me

About Lawyering—and Life

His Own Write: What John Lennon Taught Me About Lawyering—and Life

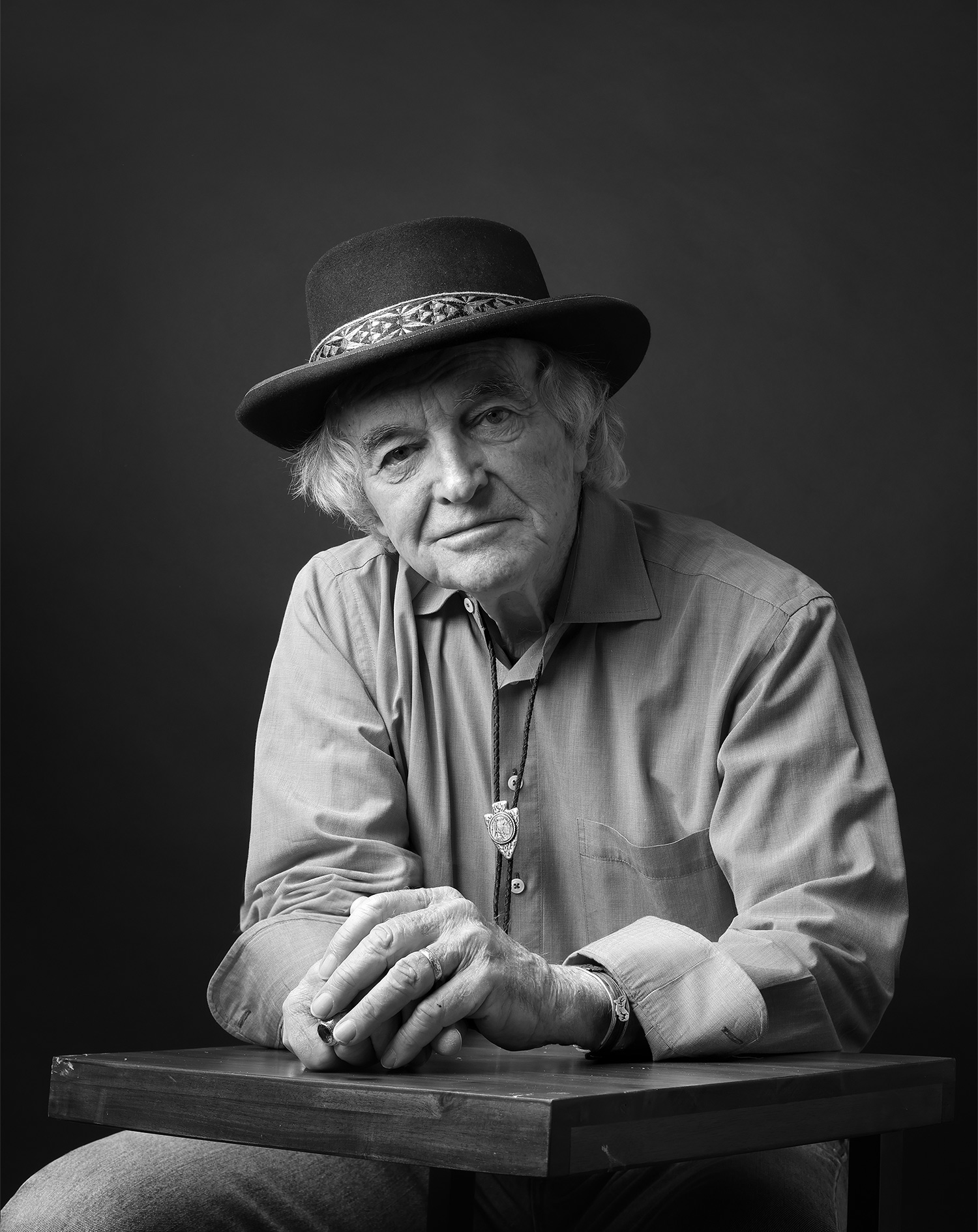

or 40 years, wherever he moved, from the New York metropolitan area to his current home in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, Jay Bergen FCRH ’59, LAW ’62, took six heavy banker’s boxes with him, transferring them from one garage or attic to another, where they continued to gather dust. “I always kept them with me, but I didn’t open them until five years ago,” said Bergen.

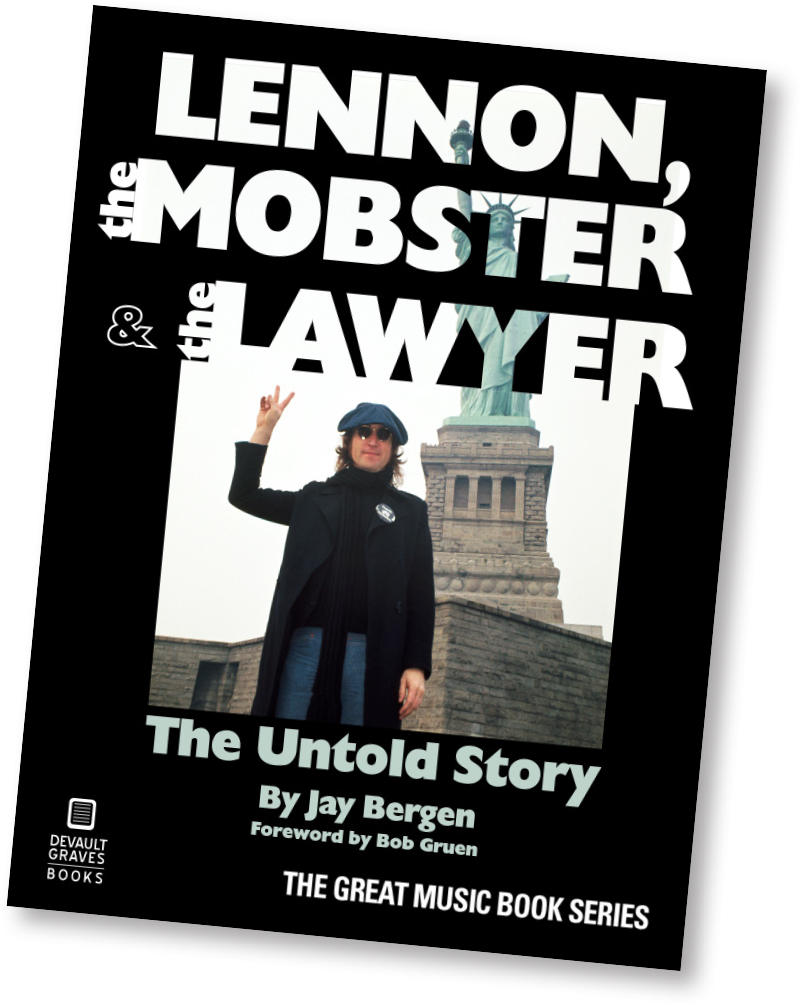

When he did, he couldn’t help but sit down on one of those boxes and lose himself in the reams of depositions and the trial and appeal records of a case he considers the highlight of his wide-ranging legal career: the two-year lawsuit he handled for John Lennon in 1975 and 1976 against Mafia-connected record company executive Morris Levy.

“When I read the transcripts from John Lennon’s testimony about how he and the Beatles became the Beatles, how they took control of the process of making an album, how they produced the covers, I realized that this was a good story—one that, surprisingly, had never really been told,” said Bergen. “And I know all the details.”

A Taste for Action

At Marshall Bratter, Bergen gained experience representing rock ’n’ roll bands. One of his first cases was representing Terry Knight, the founder and manager of Grand Funk Railroad, which was settled favorably. He then heard a rumor that the firm would be handling a new case for Lennon. “I went to one of my partners, David Dolgenos, who was negotiating the Beatles’ separation … and told him I wanted to be involved,” said Bergen.

An avid rock ’n’ roll fan in high school in the 1950s, Bergen and his first wife saw the Beatles perform at Forest Hills Stadium in August 1964. But two years after that Beatles concert, Bergen left Donovan—and Wall Street—to join a small firm on the island of St. Croix. “It was kind of like living on the moon, where you didn’t know what was going on outside a 22-mile radius and the TV went off the air at 10 p.m. while playing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’” After his marriage broke up, Bergen returned to Wall Street and to Donovan with a new spouse, who wasn’t a fan of rock music. “There was a gap of about seven or eight years when I stopped listening to [rock ’n’ roll] completely,” said Bergen.

Levy, said Bergen, was known for frivolous lawsuits and getting big-name music clients to settle—and John Lennon was now in his sights. Levy had previously sued Lennon in 1970 for copyright infringement, claiming a similarity between the lyrics of Chuck Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me,” whose catalog Levy owned the rights to, and the Beatles’ “Come Together.” As part of the settlement, Lennon agreed to make a record containing three Levy-owned rock oldies. However, Levy became incensed when Lennon recorded only one of those songs on his next album, 1974’s Walls and Bridges. To prove to Levy that his forthcoming album would contain the promised songs, Lennon handed him a far-from-perfect demo tape of the record he was working on, which he planned to call Rock ’n’ Roll and release under the Beatles’ Apple Corps label, which had a distribution deal with Capitol Records and EMI Records. Levy took that tape and released the unauthorized album, claiming that he and Lennon had a gentleman’s agreement for him to do so. In response, Lennon immediately finished and released the legit album, and Levy then sued for $14 million. Lennon and Capitol/EMI countersued, with Bergen heading up Lennon’s legal team.

While Bergen said he never feared for his own life, he was a bit starstruck to be working with the John Lennon. “When John walked into the conference room at Capitol Records and I met him for the first time, I thought, ‘Oh, wow!’” To Bergen’s surprise, Lennon turned out to be a bit shy, even a homebody, dressed in thrift store clothes. “He was the kind of person who didn’t want to let anybody down. And he always signed autographs, except when he was in the middle of eating at a restaurant. He would politely ask fans to wait until he finished.”

Bergen recalls that Lennon didn’t much care for “lawyer and accountant types,” but the two soon forged a personal connection, partly through their shared love of rock music. “After I expressed interest in the case,” said Bergen, “David Dolgenos gave me some Lennon, Beatles, and other rock ’n’ roll records to bring home. I hadn’t listened to rock in a long time, and when I put them on the turntable, I thought, ‘This is what I’ve been missing. I’m back where I belong.’”

“The Best Witness I Ever Had”

Since the judge was a music lover, however, Bergen and Lennon decided to give him “a tutorial” on the Beatles and on Lennon’s career. “On the witness stand, John would give these long colloquies with the judge, who would ask penetrating questions. The judge dismissed Levy’s claim against John of breach of an oral contract. At one point, the judge said, ‘Look, if you’re going to prove your case and Capitol/EMI’s claim that your career was damaged by the Roots album, you’ll have to show me evidence of that.’”

Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono, came to court for 20 days, parking their limousine outside of Bergen’s office building. “The first day, I asked them what they wanted for lunch, and John said, ‘We’re only eating fish.’ So, I took them to the Fulton Fish Market and pulled up at Sloppy Louie’s. It was kind of a dump, but the seafood was very good, and we went there every day after that.”

Bergen’s strategy worked: While Capitol/EMI settled their claims with Levy separately for $170,000, after Levy’s appeal, Lennon was awarded $78,000 in damages. Levy also had to turn over all of the unsold Roots albums and eight-track tapes. “I remember going up to John and Yoko’s apartment at the Dakota and giving Yoko all the boxes,” said Bergen, who credits the victory to Lennon himself. “John was the best witness I ever had,” he said. “For one thing, he was telling the truth, and Levy was not. That’s what I told John from the beginning—‘Levy’s story isn’t going to hang together.’ I also think that John had been interviewed by the media so many times that he was very [experienced] answering questions and [being] in front of a crowd.”

Bergen also points to a few other fortuitous pieces of luck along the path to the Lennon trial, without which he might never have become a lawyer at all. “I went to Fordham University, and in my last year, my roommate and I were talking about what we’d do after graduation,” he said. “I didn’t have a clue.” However, encouraged by a roommate already planning to become an attorney, they applied to law school together. Bergen was waitlisted at Fordham Law, but a recommendation from his uncle, John McIntyre, helped push his application ahead. Bergen also credits William Hughes Mulligan, then dean of Fordham Law School, with giving him the chance to prove himself.

And prove himself he did. “At that time, I was living at home on Long Island,” Bergen said. “I remember walking upstairs to my room after my first day at Fordham Law, lugging a pile of case books, and [hearing] a little voice saying to me, ‘If you screw this up, you’re in big trouble.’”

He got into the habit of studying for five to six hours a day, learning “what it took to really apply myself.” In those years, Fordham Law was located downtown near City Hall and was mostly a commuter school, but it had a close-knit community. “We had this tiny library there, and I remember seeing [future Dean] John Feerick [FCRH ’58, LAW, ’61], who was the editor-in-chief of the Law Review, running around pulling books off the shelves and checking citations,” Bergen said. “He made a big impact on me.”

Though Bergen didn’t make Law Review himself, he did get a clerkship when he graduated, thanks to his hard work and, once again, a fortuitous family connection. His aunt, Grace Tierney, would often have dinner with her Bronx neighbor Chief Judge Sylvester J. Ryan, LAW ’17, of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. “One day, Judge Ryan asked [Tierney] what my plans were for after law school,” said Bergen. “My aunt said she wasn’t sure I had any. So the judge asked, ‘Why don’t you have that nephew of yours come see me at the courthouse?’” When Bergen visited, Ryan offered him a clerkship on the spot.

That opportunity set Bergen up for the big Wall Street firms that would eventually hire him, and he never forgot the people who had put in a good word to help him get there. “About 10 years ago, my wife of 25 years [DiAnne Arbour] and I established scholarships in the names of Grace Tierney, my uncle John McIntyre, Judge Ryan, and William Hughes Mulligan,” said Bergen. “Without those four people, I would not have gotten into Fordham Law or had the career I did.”

A Law Career Is a River

Fate was in their favor. But once the trial was over, Lennon retreated, for a time, from music and public life. “Sean [Lennon] had just been born, and John really wanted to devote a lot of time to his new son,” said Bergen. “He felt guilty that, because of everything that had happened with the Beatles in the ’60s, he hadn’t been around for Julian [John’s son from his first marriage], so John became a househusband and turned their business over to Yoko.”

Though Bergen didn’t see Lennon again, the Beatle’s influence on him was profound. “I’ve always been aggressive as a trial lawyer; I know when to push,” he said. “But not so much in my personal life. … One of the things I learned from John is that you have to do the things that you want to do.”

Indeed, about five years after the Lennon trial, Marshall Bratter collapsed, one of the first New York City big law firms to do so. “There I was, married, with two kids, and it was over,” said Bergen.

Bergen started a small firm in SoHo, where he kept his hand in the music business. “It was fun, but I had to get out of there because we spent too much money on the space,” he said. Bergen moved on to a litigation and medical malpractice firm, Bower and Gardner, and took on famed Yankees owner George Steinbrenner as a client. “Eventually, he fired me like he fired everyone else,” he laughed, “but not before I left Bower and Gardner, because I realized that it was going to go bankrupt, which it did.”

Yet despite the setbacks, Bergen, who retired in 2008 at age 70, feels he had a wonderful career. When asked if he has any advice for young lawyers, he said, “You have to keep moving. A law career can be like a river. You have to follow it wherever it takes you. And if you don’t like what you are doing, if work feels difficult and painful, trust your instincts and find something else. Your legal training will always stand you in good stead.”