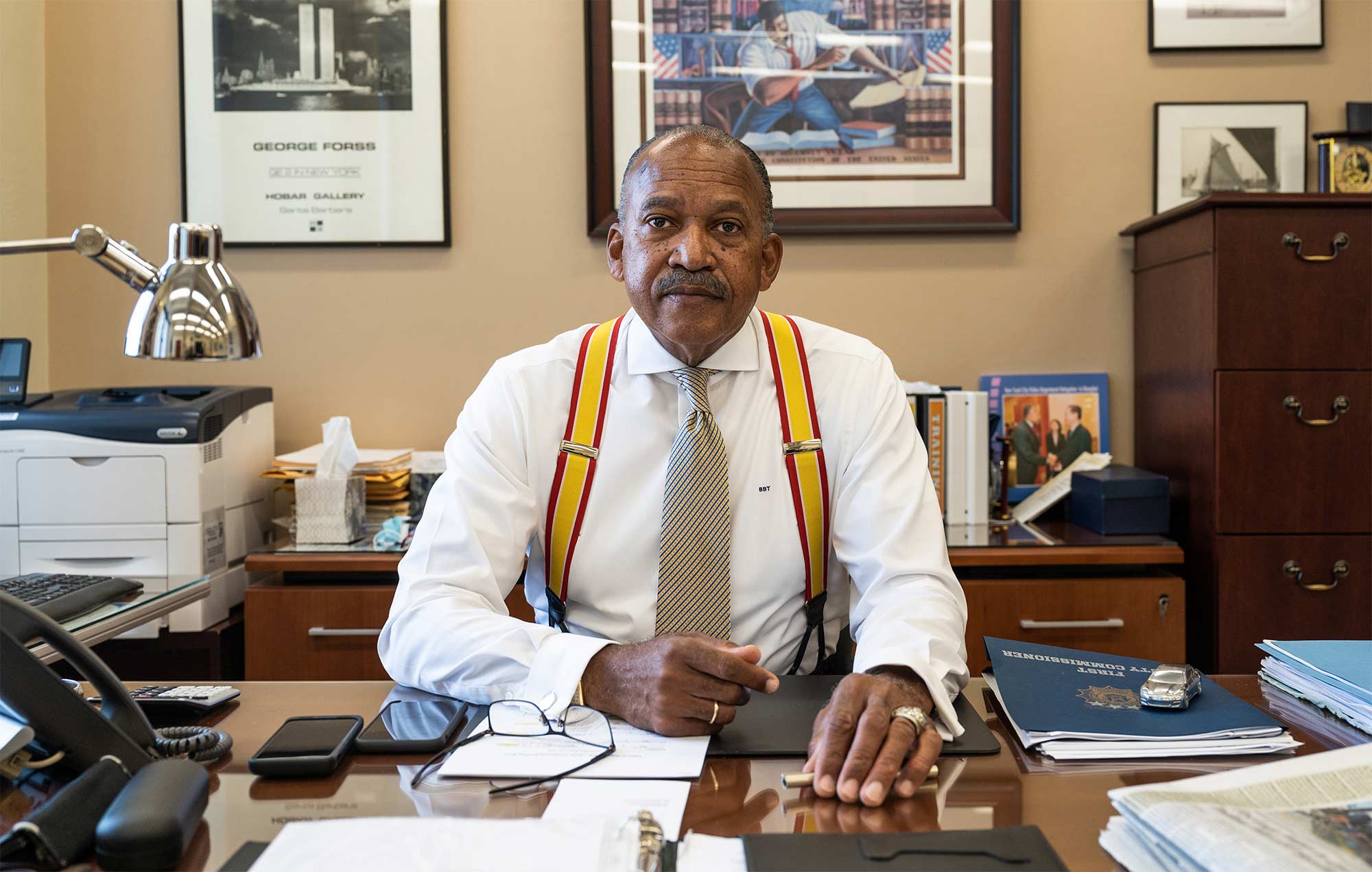

p on the 14th floor of the fortress-like New York Police Department (NYPD) headquarters in Lower Manhattan, First Deputy Commissioner Ben Tucker ’81 extends an elbow in greeting, his silver Fordham insignia cufflinks glinting in the light from his window with a view of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Because of COVID-19, Tucker has had to retire his famous strong-as-steel handshake. The elbow bump replacing the two-handed vice grip is not the only thing that’s changed for Tucker and his department in the past few months.

Tucker, second-in-command at the NYPD and the highest-ranking African American in the department, has witnessed the sweep of history—the race riots, the heroin plague, the crack epidemic, the infamous stop-and-frisk policy and its dismantling. But the tumult of 2020—from the pandemic to the worldwide police protests over the killing of George Floyd—has left him stunned.

“I thought I’d seen it all,” says Tucker, shaking his head. “But this is like nothing else I’ve ever seen, ever. It’s surreal.”

Day after day, on his way to work from his apartment in Battery Park City, Tucker witnessed thousands of protestors swarming across the bridge, calling for the defunding of the department. Just downstairs from his office, protestors occupied City Hall Park, scrawling ACAB (All Cops Are Bastards), drawings of pigs, and the words “Kill all cops” across the Tweed and Surrogate’s courthouses. Following complaints of the NYPD’s heavy-handed tactics, Tucker and his boss, Commissioner Dermot Shea, disbanded the department’s plainclothes anti-crime units across the city in June. Legislation was immediately adopted to do away with the so-called shield law—making disciplinary records of officers readily available to the public for the first time. Though it’s far from defunding, $1 billion was shifted from the department’s $6 billion budget, pulling officers from school safety, illegal vending, and homelessness duties.

Because of Tucker’s unique perspective and years of service, some in the city thought Mayor Bill de Blasio should have promoted him to head of the department last year when Commissioner James O’Neill stepped down. Tucker was among them. “I was disappointed,” says Tucker about being passed over. “But it’s the mayor’s choice. Maybe I’m too outspoken, but I’m too old to be biting my lip.” Tucker speaks with Commissioner Shea each day, helping him strategize during one of the department’s most difficult periods.

Though he’s been shocked by some of the things he’s seen in the past few months—officers under attack in Harlem, peaceful protestors roughly shoved by police—he was not all that surprised at the reaction. “As soon as I saw that video of that officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck, his hand in his pocket, how little he thinks of this human being, I was shocked. But then I was angry,” says Tucker. “There was no doubt in my mind that things were going to get crazy out there. There was this passionate outrage that I could clearly understand. Enough already. Year after year after year.”

Swiftly and strongly disciplining the officers who overstep the line from reasonable force to brutality is incredibly important, he says. “We have 36,000 officers,” he says. “They have integrity. You have the jerks that do bad things, and the truth is there will always be those people no matter how well we train them and how many bills you pass. We are human beings. And somebody’s going to do something that is wrong. You just have to hold them accountable when that happens.”

He believes the bad old days of closing ranks around those offending officers are over. And he says he is proud of “our cops,” as he calls them, and feels they showed incredible restraint in the face of the protests.

“The people want their pound of flesh,” he says, of the more violent members of the crowds. The bottles. The bricks.

In light of the protests, the department is considering disorder-control training—how to react to violence in the streets—for all its officers. “It’s a very fine line, and we’re trying to balance it,” says Tucker. “You have to keep morale up, but you have to treat people with respect. You have to strike the proper balance. That has to be the North Star on what we do as police officers.”

That attitude prompted former Commissioner William Bratton to bring Tucker back to the department in February 2014, after stints working for the Clinton administration under former attorney general Janet Reno, and for the Obama administration, helping to fight the war on drugs. After Garner was killed in July of 2014, Bratton quickly promoted Tucker to first deputy commissioner. A month later, two officers were assassinated in their police cruiser in Brooklyn, plunging morale in the department to an all-time low. “It was not just a matter of the race or ethnicity of the person,” says Bratton of his hiring Tucker. “He was the right person—someone the officers look to as a mentor and guide.”

His five decades of experience within—and outside—the department make him especially qualified to handle its new challenges. “He comes across as gentle,” said the late Charlie Adams ’81, who studied with Tucker at Fordham Law and worked with Tucker on the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) in the 1980s. “But he has teeth, and he knows how to use them.”

The path to the 14th floor was not always a straight or obvious one for Tucker, who grew up in the Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, raised by a single mom, three older sisters, very strong grandparents, and several aunts. He helped support the family while in school, shining shoes, delivering newspapers, and working in the local supermarket managed by his estranged father. When he was just 17 years old, Tucker got a knock on the door of his family brownstone when a friend came by to ask if he wanted to take the police exam with him.

Young and about to marry his high school sweetheart, Diana, he decided to join the force. “Any ambivalence I had about the police department was erased by the practical imperatives of having a job,” he says. Another reason to join the force was the free college education that would come along with it through the Law Enforcement Education Program. Tucker was married in October 1969 and became a police trainee in November. He started taking night classes that following January at John Jay College.

At first, some of his Black friends refused to speak to him for his decision to join. “It wasn’t as if they were wrong,” Tucker acknowledges. “Our experience as Black kids with police was not good. They didn’t respect us.”

Tucker was in a unique position to try to change that perspective, even then, when he was tapped to work in New York City’s schools, first to warn students against drugs, then to address racial violence resulting from busing and integration in Canarsie and Flatbush, Brooklyn. During riots in and around Brooklyn’s Madison High School in December of 1973, Tucker became the victim of the same tensions he was trying to quell.

The offending policeman eventually turned himself in and was put on desk duty for a few months. As for Tucker, the incident, instead of leaving him resentful, made him stronger. “Most of the cops in those days were male and white. And a good percentage were Irish,” he said. Back when he was a trainee, Tucker decided he would be the best cop he could be “to prove that not every kid who looks like Ben Tucker is out there doing bad things.”

After attending night school over seven years, Tucker enrolled in Fordham Law School’s evening program in 1977, working days in the 69th precinct in Canarsie, and sleeping five hours a night if he was lucky. On weekends, he’d roll out of bed at 6 a.m. and start briefing cases, getting an early start so he could spend a few hours with his wife, Diana, and son, Scott. “Law school helped make me a better thinker and writer,” he says. “It helped me have a more pragmatic understanding of things. It gave me a better perspective on how to solve problems.”

Tucker also connected to the community at Fordham. Neil Blackshear ’77, an NYPD lieutenant who graduated from Fordham the year Tucker started and went on to become a bankruptcy judge, was one person who helped Tucker navigate his years there. “He made sure I knew what to expect—the workload, the classes,” he says. Tucker also appreciated Fordham’s historic emphasis on having a diverse student body. “Fordham understood the value of having African American students among their population,” says Tucker. “It just makes sense. You have to have lawyers who look like people in the communities they serve.”

After law school, Tucker taught constitutional law and criminal procedure in the police academy, then transferred to the NYPD Legal Bureau as a legal advisor. In 1983, he became assistant director at the CCRB, where he oversaw investigations. “In some cases, an investigator made one phone call and got a busy signal and didn’t call back. That was that.” Tucker sent back 60 to 70 percent of cases to be investigated again. He hired new investigators to review cases with the promise of a detective badge after 18 months of service. He also computerized complaints so they couldn’t magically disappear. “Ben is incredibly fair and thoughtful,” says Barbara Gunn, who worked for him in the mid-1980s in the mayor’s office of operations. “He cares deeply about the police department, what it does, and how they do it.”

Tucker then followed Jeremy Travis to Washington, D.C., where, under Janet Reno, he was tasked with directing billions of dollars to local and state police organizations. Later, working for President Obama under drug czar Gil Kerlikowske, Tucker helped shift the public policy focus from drugs as a criminal problem to a public health crisis. In 2010, seeing the growing problem of opioids, the office also issued the White House’s first prescription-drug strategy. “Ben has this charisma, but without bullshit,” says Kerlikowske. “It’s truth-telling in a way that is really, really impressive.”

Tucker says that working outside of New York City and traveling widely to oversee drug policy gave him newfound perspective. Simply seeing the drug problem not just on the street level, but from the country’s borders, gave him a better understanding of how the drug trade worked. Yet when Mayor de Blasio was elected and began assembling a new team, Tucker started thinking that maybe it was time to return home.

Then came Eric Garner. After he was killed, Tucker and Bratton asked the mayor for $30 million to retrain the entire police force. Veteran officers are now required to have three days of new training each year. Cops were also placed on the street for more hours, rather than patrolling in cars, to help forge better relationships within the community.

One of Tucker’s jobs has been convincing the force that body cameras are a benefit for all. “They change the officers’ behavior, but also citizen behavior,” he explains. “For instance, when an officer stops a car, you identify yourself and the reason you’re stopping that person and then, ‘By the way, I’m recording this.’ That brings the temperature down right there.”

Videos of active crimes—from body cameras, but also from thousands of surveillance cameras throughout the city—also make the DA’s job easier, he says. “You’re documenting events in real time,” he says. “If you see a crime being committed on video, it’s easier to prosecute.”

Facial recognition technology is another controversial topic which many fear will lead to false arrests and racial profiling, “First of all, we use it sparingly,” says Tucker. “Not just to I.D. people but also to eliminate them as suspects.” The days of numbers-driven policing, he says, are over. “We’ve proven you can be very precise about going after those people who deserve to be in prison and who are the most violent, and not do these dragnets and harass everyone else.” All of this helps improve community relations—which is crucial in helping bring more citizens forward to identify the criminals in their own neighborhoods. The Community Partnership Program started under Tucker’s watch in 2014 has citizens hosting new cops coming straight out of the academy, educating them about the neighborhood, and introducing them around. Its mission has never been more important, though the newest class of cadets was canceled by the mayor in July, reducing the police head count by 1,194. “I’m worried about that,” says Tucker. “We’re starting to see an uptick in retirements, and we need those cops out there.”

Tony Clemente, an officer who worked with Tucker in the mid-1980s and is now a deacon at a Brooklyn church, says it’s Tucker’s ability to keep the peace that endears him not only to his fellow members of the NYPD but to the public. “I always told him he should have been a priest and not a cop,” says Clemente, who tells the story of marching in Canarsie, Brooklyn, back when the neighborhood was mostly Italian. Residents had protested a Black family buying a house there; Al Sharpton was leading a counterprotest; and Tucker and Clemente were brought in as escorts. “People were screaming horrible things, throwing bananas and calling us monkeys,” remembers Clemente. At one point, Tucker went over to the barriers and approached the enraged white crowd to try and calm them down. “I was thinking, ‘How could you even talk to these people?’” recalls Clemente. Apprehensively, Clemente watched as Tucker went into the crowd and started talking. “To this day, I don’t know what he was saying to them, but immediately, they started to listen.” He pauses. “The voice of reason. And he’s still that man.”

Tucker believes the city and the force have come a long way since those days of racial strife and record killings. Though with the recent protests over George Floyd’s death, it’s like starting from square one. “But we’ve done our due diligence,” he says, “and have to make sure that sort of thing never happens again.”