does one transition from the arts world to the legal world?

does one transition from the arts world to the legal world? does one transition from the arts world to the legal world?

does one transition from the arts world to the legal world? does one transition from the arts world to the legal world?

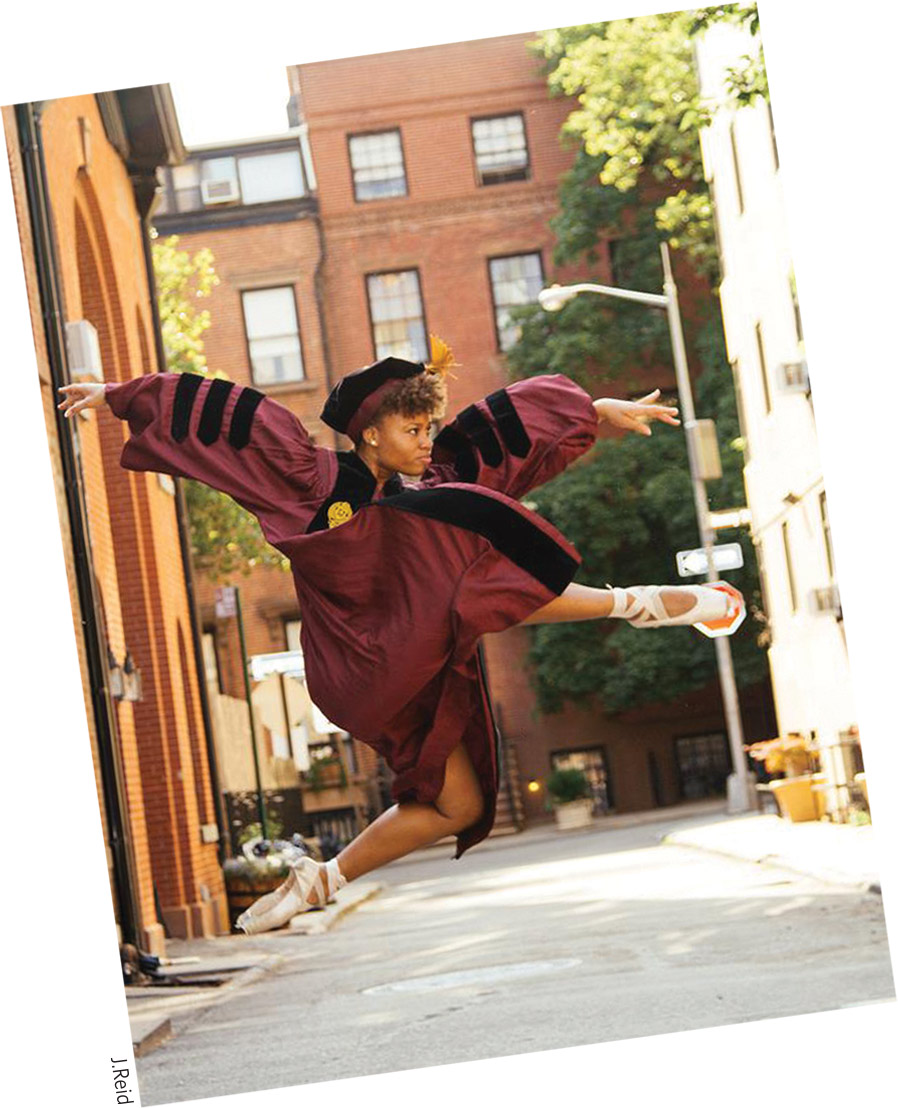

does one transition from the arts world to the legal world?The career shift from performance to public policy was initially propelled by the aches and pains that come with dancing for a living. “By the time I was 28, I had severe tendinitis in my toes and in my hips; I’d been dancing for 25 years and my body was saying, ‘That’s it,’” she says. “But I realized that working as an artist, I’d built business management skills. I’d read contracts, managed a complex schedule, and had so much experience negotiating a fair deal.”

Indeed, when fellow dancers in one company she was in began having contract issues, they urged her to do the talking. “We were about to go on tour and were rehearsing during the day and performing at night,” recalls Dunlap. I told management, ‘This is way more than an eight-hour day.’ The operations person’s face just froze. He said, ‘How do you know that?’ It was because I knew the law!”

And that was before law school. “I realized that as a lawyer, I could be even better at business management and understanding the protections and rights workers have.”

Once she was enrolled at Fordham Law, Dunlap realized that her background as a dancer gave her an advantage. “Performing artists tend to be super organized, competitive people,” she says. “To do our job, we have to walk in feeling like we’re the best of the best. We have to cope with rejection. We have an incredible work ethic; our classmates will complain about the amount of reading while we’re saying, OK, if I get up an hour earlier than everyone else … It’s impossible to hide a lack of work in dance. We can see everything.”

Dunlap also urges Fordham Law’s performers-turned-1Ls to “lean into the things that made you a great artist. When other people say, ‘I went to Wharton before law school!’ or, ‘I was an engineer before law school!’ you can say with pride, ‘I was an artist!’ That takes rigor and excellence.”

She also suggests they draw on examples from their previous careers when tackling the challenges that law school brings. “You can often say, wait a minute, that incident when I was a performing artist was a civil rights issue or a constitutional issue or a contracts issue.” Just as important, she says, is not abandoning their art. “I still dance every day,” she says, “whether at home, on the subway, or when I go for walks. It’s part of my being.”

Here, snapshots of four 1Ls who are following in Dunlap’s footsteps.

I toured with Itzhak Perlman when he conducted the Juilliard Orchestra at David Geffen Hall and in Chicago. I also spent a month in Finland and got to play at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, among other things. I toured India with the Yale Schola Cantorum and was even sent to Bolivia last year as an arts envoy for the U.S. State Department. It was all beyond my wildest dreams.

the turning point: I’d come to New York City to follow music—I wanted to see how far I could take it. I thought I’d perform in the city through my 30s, but even when I was performing alongside incredible musicians at the peak of my playing career, it felt like something was missing from my life. I’m from Anchorage, and all along, I knew that law would be the path that would get me back home. I’m fourth-generation Alaskan, and there are no law schools in Alaska, so I’d be attending law school out of state no matter what. I’d hoped to go to Fordham from the beginning. For one thing, it’s right at Lincoln Center so I already knew which coffee shops I liked.

dipping into law, to help other artists: In 2018, I started work as a paralegal at an immigration firm, doing Extraordinary Ability visas, a special visa category for people at the top of their profession in the arts, and also the sciences, business, and technology. Initially I was interested because of my background in music, but the job became much more than that. My first green card application was for a very accomplished photojournalist. There I was, at the beginning of my legal career, helping make it possible for her to continue her career here. I also did artist visas for people I’d done gigs with—people who had come to this country to contribute their skill to our talent pool. Without an Extraordinary Ability visa, they wouldn’t have been able to do that. Advocating for these folks—having one foot in the music world and one in the immigration world—it was all very gratifying.

an eye to the future: It was cool and unexpected to experience that nexus of music and law while working in immigration. But there are not many opportunities in the arts and law back in Alaska, so I’m thinking about going into corporate governance, maybe mergers and acquisitions, or dealing with the issues of corporate social responsibility, sustainable development, and environmental law that make such a direct impact on many communities in my state.

filling a need: As a musician, I could see all the ways musicians need the law. Some don’t know how to advocate for themselves. Many don’t know how to read a contract—often they are not even given a contract. I got very upset by the way things are in the music business, but with law, even if I lose, I can try to fight injustice. If you’re in music, sometimes you can’t even try because of the politics, because fighting something could hurt your career in the long run.

an eye to the future: I would like to do corporate law and combine it with entertainment law. The more classes I take, the better idea I’ll have. But I am still an active performer, and I usually play at Lincoln Center with the American Classical Orchestra. We perform music from the 17th to 19th centuries, using period instruments and techniques. In the future, I’d like to continue to play and maybe have a few violin students.

the turning point: Three years ago, I thought, I am five years younger than my mom was when she had me. I love this career, but it’s not providing the lifestyle I want to give my kids someday. At this point I was in the 98th percentile of earnings according to union statistics, but I’d never made more than $30,000 in a year. That’s how hard it is to make a living in theater. So I started talking to myself about what else might be interesting. I can cry on cue, but I don’t know much about Excel. I didn’t necessarily want to perform anymore, but I still love the biz, so I decided to get an M.B.A. at Gabelli. In my last year I took Employment Law with Lori Rassas at the Law School. It had everything to do with what I’d learned as a union liaison on so many of my gigs, as well as employing artists, which is essential to the industry. I totally found my happy place—and I hadn’t even known it was a thing!

an eye to the future: I imagine my perfect career as in-house counsel at an entertainment union—I want to stay close to arts and continue advocating for performers. But who knows? Check in with me when I’ve got more than two courses under my belt.

Cultivating a new passion: While working at a classical music management company in 2016, I happened to read a book about George Washington by Ron Chernow. I discovered I loved reading about U.S. history, and decided that I would read a book about every president, going chronologically. Well, you can’t learn about U.S. presidents without learning about precedents of law in the United States. That’s when I realized that law school was exactly the right thing.

How his background helps him now: Pianists are known for the absurd amount of time we spend practicing. A singer can only practice a certain amount before they lose their voice, but a pianist, if they’re motivated, can practice a lot. As a result, I do everything with extreme focus. That determination is necessary to be proficient at an instrument. Now I’m using the same tools to put law school concepts together and see how they build on each other. It’s all about building blocks.