Traveling Judges

116 American Journal of International Law 477 (2022) [with Alyssa S. King]

By Alyssa S. King* and Pamela K. Bookman**

Introduction

***

“Traveling judges” are those who ***travel from their home jurisdictions to serve on another jurisdiction’s court.*** This Article begins the study of traveling judges on these courts by identifying who they are, where they serve, and what roles they play. In some ways, they repeat old patterns. Traveling judges are overwhelmingly from the UK and former dominion colonies. They are less diverse than international arbitrators and far more likely to have judicial experience. A look at their backgrounds suggests that traveling judges might be a phenomenon limited to common law countries, but only half of hiring jurisdictions are in such states. Almost all, however, are or aspire to be market-dominant. Traveling judges offer hiring jurisdictions a method of transplanting well-respected courts, like London’s commercial court, on their shores.***

The stakes are high. As these courts proliferate, they are poised to exert increasing influence over dispute resolution, law development, and global judicial governance. Traveling judges may improve international commercial dispute resolution around the world, promote rule of law values, and contribute to convergence in commercial law or even civil justice. But they could also promote a neocolonial world order that harnesses certain jurisdictions’ sovereignty to sustain a commercial law that benefits some multinationals at the expense of the global community more broadly defined.1

A better understanding of traveling judges will contribute to studies of judges, judicial identity, and judicial legitimacy, among other areas. Private international law and international economic law scholars may study these courts and their judges’ role in promoting foreign investment, the market for law and dispute resolution, and the harmonization and convergence of international commercial law. Historians may appreciate traveling judges’ implications for the legacy of colonialism and the legal origins debate. Political scientists may view traveling judges as a window into debates about democratic accountability, institution building, and legal transplantation. And legal scholars more generally may be interested in what this phenomenon reveals about the development of public and private law, the boundaries between them, and the relationship between international dispute resolution and national sovereignty.

This study focuses on traveling judges on courts that handle international commercial disputes, in particular members of the Standing International Forum of Commercial Courts (SIFOCC).2 We determined which SIFOCC member courts hire traveling judges, collected extensive information about the courts and the judges,3 and interviewed over twenty-five judges and court personnel. This study uses grounded theory4 to contribute to the growing methodological fields of empirical and social science approaches to comparative law and international law. It also incorporates legal history to develop explanations for why these jurisdictions hire these traveling judges.

Out of forty-four SIFOCC members, nine employed traveling judges as of June 1, 2021.5 In addition to the Hong Kong SAR judiciary, this group includes the Singapore International Commercial Court (SICC), a division of the high court of Singapore with jurisdiction restricted to international commercial disputes; four court systems for new special economic zones (SEZs) in oil-exporting states—the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC), the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM), the Qatar Financial Centre (QFC), and the Astana International Financial Centre (AIFC) in Kazakhstan—all of which limit jurisdiction to civil or commercial disputes; two commercial courts in the Caribbean—the Cayman Islands Financial Services Division (a division of the Cayman Islands Grand Court) and the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court (for which we focus on the British Virgin Islands (BVI) Commercial Division); and the Supreme Court of the Gambia.

To make sense of this list, this Article identifies the common features of these jurisdictions and their courts, while acknowledging their many differences. Half are located in common law countries. All but one are in former British colonies or protectorates.6 The jurisdictions in this study—including the SEZs in the oil states—all follow the common law tradition. Either by way of colonial legacy or by recent legislation, these jurisdictions have adopted substantive law and procedures that mirror those in London to varying degrees. The most commercially oriented courts are in jurisdictions that are or aspire to be “market-dominant” with an outsized influence in global finance. Political and judicial leaders in these jurisdictions have designed these courts for cross-border disputes, anticipating transnational parties.

Some courts have only a few traveling judges on a mostly local bench. Two courts employ 100 percent traveling judges.7 As of June 1, 2021, we identified seventy-two sitting traveling judges on all courts included in our study. Several judges sat on two or more courts.8 They were overwhelmingly white, male, retired judges. Nearly seventy percent also acted as arbitrators, often spending more time as arbitrators than as traveling judges.

Considered as a group, the traveling judges reveal a stark British influence. Most have some UK-based legal education. About half are from England and Wales. The remainder come from other common law or hybrid jurisdictions, with no single jurisdiction providing more than five traveling judges, and most providing only one or two. Despite the prominence of New York and Delaware commercial law, we found only one U.S. traveling judge.9

The demographics of traveling judges reflect the way hiring governments seek to appeal to foreign investors, which in turn reflects not only colonial history but also the rise of international commercial arbitration and perceptions about what legal environments are most business-friendly. Judge demographics also reflect constraints on sought-after individuals’ willingness and desire to serve as traveling judges, which may be informed by their home jurisdictions’ judicial retirement age and by judges’ post-retirement career options.

In addition to these empirical and analytical contributions, this Article examines some implications of our study, all of which reveal a reassertion of state power in international commercial dispute resolution. First, traveling judges’ demographics reflect the hiring jurisdictions’ use of the English common law tradition—and its judges—to further their foreign investment goals. Our results undermine arguments that transjudicial global networks are becoming less dominated by earlier hegemonic powers10 and support studies of the domination of English common law in the coding of global capital, linking today’s legal arrangements to colonial history. Second, although traveling commercial judges resemble international arbitrators, comparing those groups suggests that hiring jurisdictions prioritize certain elements—including judicial experience and nationality—differently than parties do when appointing arbitrators. Third, different host governments and local circumstances may create obstacles to the courts’ ability to achieve their various goals and to traveling judges’ ability to judge in the ways they may be accustomed to judging in their home jurisdictions.

***

I. Traveling Judges and Commercial Courts

II. Methodology

A. Selecting the Courts

***

To capture the universe of courts that have or aspire to have substantial cross-border commercial dockets, we examined courts that self-identified as such by joining the recently created SIFOCC.11 ***SIFOCC membership is open to institutions from any jurisdiction “with an identifiable commercial court or with courts handling commercial disputes.”12 Member courts all self-identify as courts that “hear and resolve domestic and/or international disputes over business and commerce.”13 Membership thus provides a serviceable way to distinguish which courts consider themselves commercial and engage with foreign counterparts. The recent spate of specialized international commercial courts are all SIFOCC members.14 Members also include domestic courts or divisions with large percentages of cross-border commercial cases, like the London Commercial Division, the Cayman Islands Financial Services Division (FSD), and the Supreme Court of Delaware.15 Most are first instance courts, although some are appellate courts or high courts, which include both trial and appellate divisions.16 Most SIFOCC member courts are common law courts, even if they are not located in common law host states.17

***

B. Classifying the Judges

Focusing on these commercial courts, we then examined their benches to determine which include traveling judges. We define “traveling judges” as those judges who, at the time of appointment, are not citizens of the host court’s jurisdiction, do not permanently reside there, and did not have their primary legal career there. Courts that invite traveling judges do not require their judges to reside in the host jurisdiction before they accept the post. Traveling judges may have had some contact with the host court jurisdiction in their work as attorneys, but our definition excludes anyone who held government office, or for whom court or law firm bios or, failing that, news articles, indicate that they practiced as local lawyers. The barrister who “flies-in” regularly from London counts as traveling if appointed to the bench, but the UK born and English-trained head of the tax practice at a local firm would not.

***

C. Identifying Commercial Courts with Traveling Judges

By examining the judiciaries of SIFOCC member courts, we identified traveling judges on nine SIFOCC-member domestic courts or court systems in the Caribbean, the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Central Asia, that is, on 20 percent of SIFOCC member institutions. These traveling judges appear on some of the most innovative new international commercial courts as well as some of the busiest jurisdictions in the Caribbean.

***

D. Judge Census

We first collected publicly available biographical and demographic information on all judges for each of the SIFOCC members that employed traveling judges in June 2021.18 We identified over 120 current and former traveling judges on the relevant courts, of which seventy-two were listed as active judges on June 1, 2021. If available, we recorded the judge’s nationality, home jurisdiction, previous employment, race, gender, and whether they worked as an arbitrator, as well as dates of retirement and hiring.19 Historical information was much more readily available for some jurisdictions than for others.20 As a result, we focused on a snapshot of the courts in June 2021. The study aimed to identify who traveling judges are across a variety of metrics to aid the analysis in this Article and future studies.

E. Interviewing Judges and Court Personnel

To give greater context to the data and to understand the practical working of these courts, we also interviewed current and former judges on these courts and current and former court staff. Our aim was to speak with at least one, and ideally two or more, local judges, traveling judges, or staff from each court in the study. Most of our interviewees were traveling judges. As lawyers often rely on personal connections, we used snowball sampling and began by talking to existing contacts.21 The interviews were thus not representative, but were helpful in interpreting publicly available sources. Moreover, the interviews allowed us to understand elements of court practice that are not easily available to the public, such as judicial pay structure and case assignment. We asked participants how they came to serve on these courts, why they agreed to serve, how cases were assigned, how much time they spend as a traveling judge on each court on which they serve, and what their responsibilities are.

We spoke to twenty-eight judges and court personnel or others familiar with the working of these courts. We offered participants the opportunity to be anonymized or speak under Chatham House rules. We are unable to report totals for each court due to confidentiality concerns, but we can report that final interview numbers provided lopsided representation, favoring some courts more than others.

III. Introducing Traveling Judges

***Traveling judges on commercial courts are an overwhelmingly common law phenomenon. Almost all the traveling judges in this study spent their careers in a common law jurisdiction; all but one traveling judge holds at least one law degree from a common law country. A majority practiced in England and Wales and an even larger number studied law in the UK. Judges from outside the UK tend to travel within their own regions—but their numbers are typically too low to draw firm conclusions about their patterns of circulation. English judges, however, are everywhere.

***

A. Who Travels

***

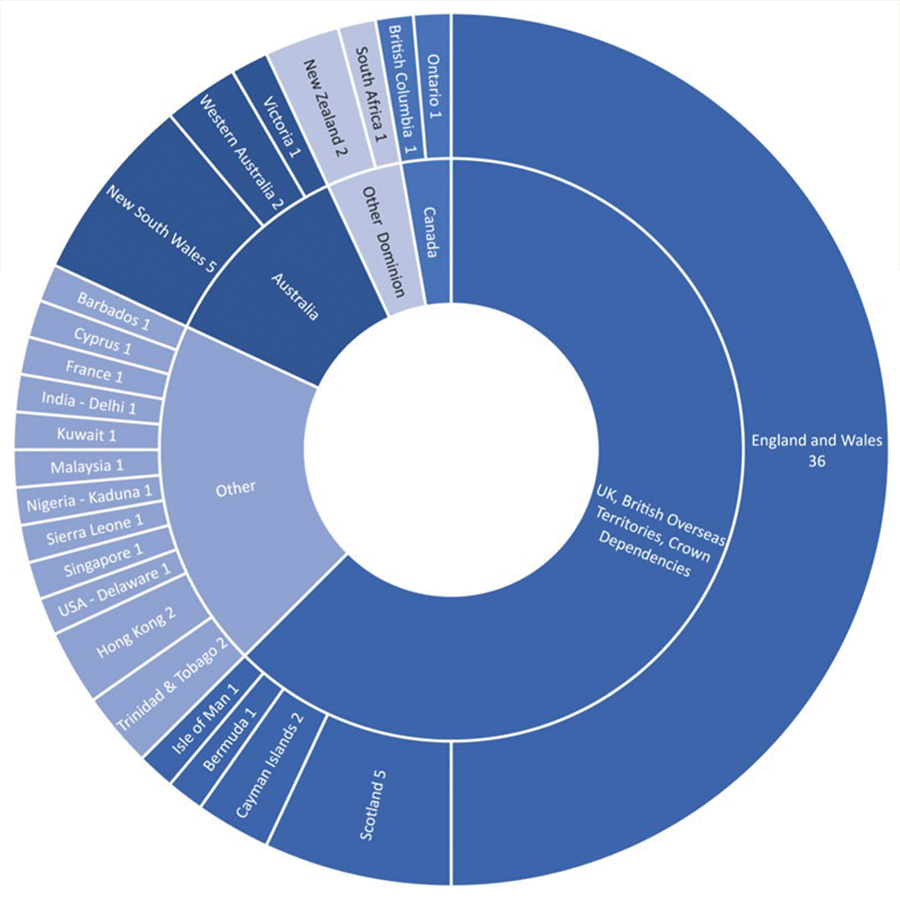

Far and away the most common home jurisdiction was England and Wales (50 percent), followed distantly by Scotland (7 percent). Australian jurisdictions came in next with New South Wales (7 percent), Western Australia (3 percent), and Victoria (1 percent). A majority of judges (60 percent) were UK nationals. A supermajority (76 percent) was from the UK or a former dominion colony (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, or South Africa). Figure 1 below shows the home jurisdiction of all the traveling judges on commercial courts as of June 1, 2021.

Figure 1 shows that traveling judges are a primarily common law phenomenon. The only home jurisdiction listed with a purely civil law tradition is France, the home jurisdiction of Dominique Hascher of the SICC.22 Six traveling judges are from countries with a mixed legal tradition.23 Still, the prevalence of common law judges is clear. In Hong Kong, the Caribbean jurisdictions, and the Gambia, only judges from common law or Commonwealth countries may serve.24 Figure 1 also suggests a break with colonial patterns in judicial hiring. Roughly twenty-five percent of traveling judges are from home jurisdictions that are not part of the UK or its former Dominion colonies.

***

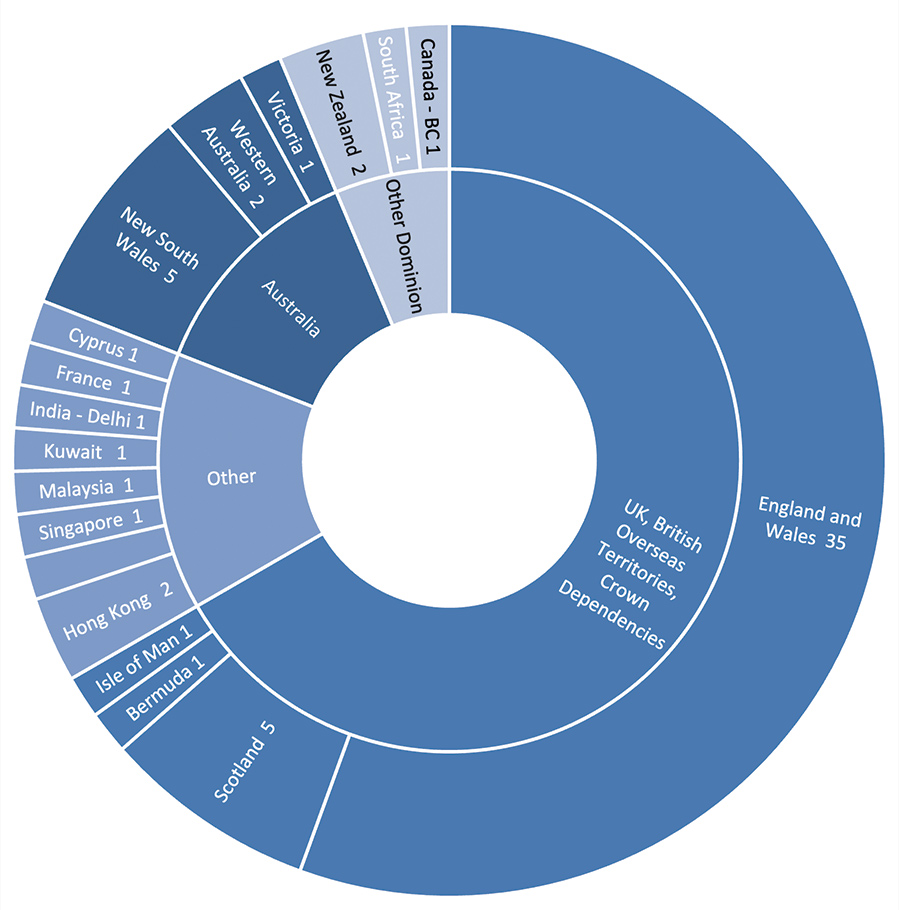

If one focuses only on the courts in our study most oriented to international commerce,25 the traveling judges look more like their colonial antecedents. Eighty-three percent are from the UK and long-term Dominions (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa). The AIFC courts in Kazakhstan have 100 percent English judges. The rest of our discussion will focus primarily on the judges in Figure 2.

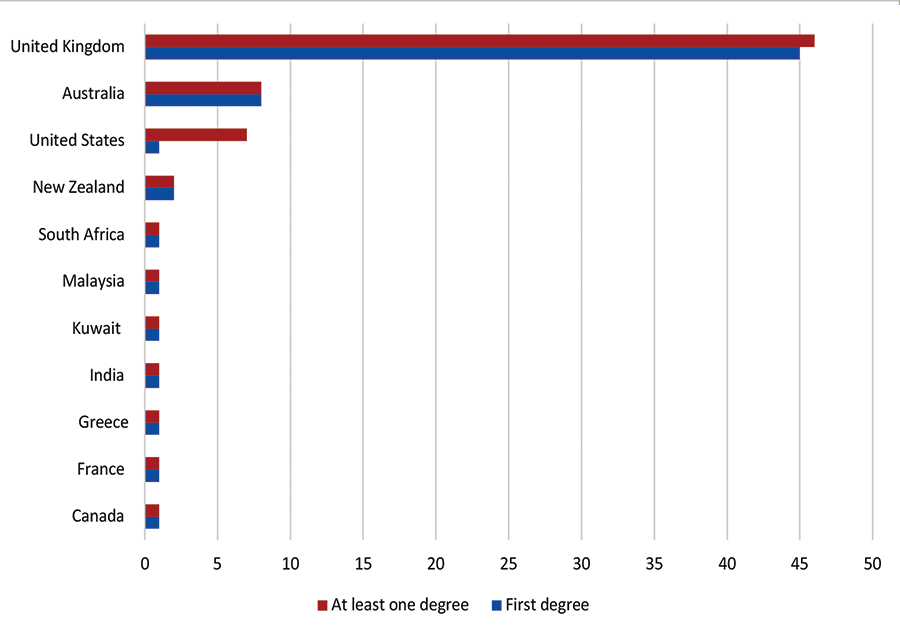

***English law influence is even more apparent when one looks at the traveling judges’ education. Of the judges included in Figure 2, forty-six (73 percent) studied law in the United Kingdom. Most judges received their first degrees in the country in which they then spent their careers (their home jurisdiction).26 Judges who went abroad for a first degree mostly studied in the UK (four judges overall).27 About a quarter of traveling judges (seventeen) held a graduate degree in law, all of which were from common law countries—predominantly the United Kingdom and United States.

IV. Explaining Traveling Judges

A. Who Invites Traveling Judges?

The collection of commercial courts that hire traveling judges is diverse along many dimensions. To understand the potential global influence and implications of the modern phenomenon of traveling judges, it is important to understand their similarities as well as their differences. These courts are English-language, common law courts often modeled on the London Commercial Court to varying degrees. The courts vary in terms of their status within their host judicial system (apex court, high court, trial court) and in the breadth of their subject-matter jurisdiction. Almost all the host countries have a history of British colonial influence, either as protectorates or colonies. These states are, again to varying degrees, interested in making their judicial systems attractive to foreign potential litigants and a global audience; hiring jurisdictions are usually established or aspiring financial or legal hubs, tax havens, or destinations for foreign direct investment. Host states of these courts are often small jurisdictions, either non-democracies or non- self-governing territories.

***

B. Why Hire Traveling Judges?

We*** assess three standard explanations for foreign judges—lack of local capacity, desire for expertise, and reputation building—and find that they offer some, but incomplete, explanations for these traveling judges on commercial courts. Beyond expertise, for example, these judges also bring elite status. We then offer an additional explanation: traveling judges offer hiring jurisdictions a mechanism for transplanting an adapted version of a successful commercial court, like the London Commercial Court. These four explanations draw together similar themes among the different courts, although they are not intended to be exclusive and they should be re-evaluated over time in future research.

***

C. Where Do Traveling Judges Travel From?

***

1. Ethics and Retirement Rules

A home jurisdiction’s ethics rules governing judicial retirement and what judges may do while sitting or post-retirement all help define who is likely to be available to serve as a traveling judge. The UK’s and Australia’s rules in these areas make serving as a traveling judge easier than the rules in the United States and Canada. These differences help explain the results of our study with respect to traveling judges’ home jurisdictions.

***

2 Legal Profession Regulations

Jurisdictions with a split legal profession may be more likely to produce traveling judges because traveling judges may join barristers’ chambers without fear of creating conflicts of interest, whereas in fused professions, potential judges often must choose between joining a law firm and serving as a traveling judge. ***These factors also help explain why few U.S. judges travel despite the prominence of New York and Delaware in international commercial law.***

D. Why Do Traveling Judges Travel?

Some may observe the traveling judge phenomenon as mercenary, but interviews and research reveal multiple reasons, including but not limited to compensation, that drive individuals to accept positions as traveling judges (or to apply for such positions). In general, traveling judge positions do not appear to be the most lucrative employment options available to these individuals.

To attract the top of the profession, most courts in this study do appear to offer robust compensation. ***From what we can gather, the hourly pay can be generous, but not necessarily as generous as that of top arbitrators or practicing lawyers. Many traveling judges, moreover, are in a second stage of their careers. As noted above, some report that they are not motivated, or not primarily motivated, by compensation.28

Judging also offers intangibles, including some power and prestige. Many report that they appreciate the opportunity to contribute to the rule of law. Judges say they enjoy the complexity and challenge of high stakes cross-border disputes. Some are intrigued by the innovativeness of the courts.29 They enjoy the chance to work with other judges around the world, and perhaps not to be bound by their home jurisdiction’s legal precedents.30 Some seem to prefer judging to arbitrating, or at least appreciate the differences between the two. As a judge, “you are the complete master of procedure,” one explained, but with arbitration, “parties expect to have a good deal more control.”31 Judges have to compromise less on process.32 The fact that being a traveling judge is often not a full-time job also preserves time to pursue other endeavors, including work as an arbitrator, judge on a different court, lawyer, or academic.

***

V. Traveling Judges in Context

***

A. Harnessing English Common Law

***As a group, about half of traveling judges hail from England, while the other half come from a variety of other (mostly common law) home jurisdictions. Over 80 percent hail from England and its twentieth-century dominion colonies (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa) and more than three-quarters studied law in the United Kingdom. These twenty-first-century legal institutions thus reflect the influence of the British Empire and its law.

The study of international commercial courts has focused on ways in which these courts are broadly “international,” but traveling judges’ identities suggest that these courts do not have a broadly international judiciary. Instead, host jurisdictions are building on both the colonial legacy of the common law and a perceived global preference for common law legal traditions.

***

B. Comparing Traveling Judges and Arbitrators

***

As a whole, traveling commercial judges are even more homogenous and have vastly more judicial experience than arbitrators, even as more than half of traveling judges also serve as arbitrators. The fact that so many traveling judges are retired judges reinforces differences between hiring courts and arbitration, countering narratives that these courts are arbitration-court hybrids.33 The lack of diversity among traveling judges can compromise their legitimacy and authority among some audiences, but it is likely intended to provide familiarity, mirroring non-diverse benches in the traveling judges’ home jurisdictions. Greater levels of diversity on certain courts, moreover, reveals the courts’ different agendas. Some more than others appear to be building a more hybrid or internationalized court.

***

C. Court Aspirations and Constraints

This Article has primarily focused on drawing conclusions about traveling judges as a group. This section focuses on the multiple differences between the hiring courts—they may have different reasons for having traveling judges, different status within the judiciary (e.g., as trial courts or apex courts), and different relationships to local government power and local political economies. These differences, in turn, affect traveling judges’ ability to facilitate investment, promote the rule of law, or transplant their home courts’ legal traditions into a foreign context.

First, jurisdictions hire traveling judges for different reasons. Some may seek to reassure investors by providing familiar law and familiar judges. Others may seek to attract regional or international litigation business itself. Different types of investors or potential litigants may have different needs, moreover, so a court that reassures investors in an SEZ may look different and have a different volume of work than a court that reassures investors looking to take advantage of local tax laws.

Second, hiring courts have different status within a local judiciary. Traveling judges may enter a local legal system as trial-court, appellate court, high-court, or apex court judges, and thereby inhabit the differing roles that accompany those posts. Traveling judges may hear cases once a year or less, or may come to serve on full-time trial courts, even if non-resident in the hiring jurisdiction. Courts in the Caribbean with traveling judges are an integrated part of the domestic legal infrastructure. ***All of these differences—and more—distinguish these courts from each other and thus distinguish the context in which traveling judges work. A full-time trial court judge in the Caribbean has a different local impact than a once-a-year appearance by an apex court judge in Hong Kong. The former may do more on-the-ground work and the latter may do more for the jurisdiction’s perception internationally. The two judges’ impact on law development may also differ.

Third, these courts—and these jurisdictions—also exist in the context of different local political economies, including different, and potentially changing, levels of government support for the court and for hiring traveling judges and expanding or contracting the court’s jurisdiction. Likewise, other domestic courts or divisions may have different levels of willingness to transfer cases or recognize judgments.

***

Over time, different goals for the courts and different political environments may lead to greater divergences both in which traveling judges a given court seeks to hire and who will accept traveling judge positions.

***

Conclusion

Traveling judges embody the link between the idea of a global community of courts, colonial judiciaries, and modern international arbitration. Their identities demonstrate the continued influence of the United Kingdom and former dominions in commercial law, but they also demonstrate how today’s judges differ markedly from the colonial judges of the past. They are far more elite and specialized. Hired, rather than sent, they trade on reputations built in their home jurisdictions’ judiciaries. Who these traveling judges are reveals much about the hiring jurisdictions, their perceptions of the desires of the international community, and the landscape of post-colonial judicial power. This Article begins a conversation about who traveling judges are, what they do, and where they are going.

Much work remains to be done to investigate court-specific and regional trends, networks between courts created by judicial travel, traveling judges’ relationship to international arbitrators, and their effects on law development. Hiring retired judges from other jurisdictions to serve on commercial courts appears to reflect not a rejection of international commercial arbitration so much as a reinvention of it within the context of the state. The implications of that re-invention also deserve further study.34 Likewise, whether traveling judges will drive increased harmonization keyed to English substantive and procedural law will also require additional research.

One might further track how judicial demographics change over time. Our study took a snapshot of June 2021. June 2031 may look much different. In February 2022, Bahrain opened an on-shore, English-language commercial court with traveling judges following an entirely different model—with a bench comprised of individuals with histories as arbitrators rather than judges, from civil and common law backgrounds, who held multiple nationalities and practiced in multiple home jurisdictions. This court could shake up the phenomenon or perhaps fizzle into insignificance.

There are also ethical implications to traveling. As we write these final words, the status of traveling judges and their ability to reassure international audiences of the stability of the host government’s rule of law, and thus to encourage foreign business in the jurisdiction, is being put to the test. Lords Reed and Hodges resigned from Hong Kong’s CFA in March 2022, but they were not the first. An Australian judge resigned in light of the Nationality Security Law in 2020. A UK judge declined to renew her post in 2021, citing personal reasons and expressing confidence in the continued rule of law in Hong Kong, “‘at least as far as commercial law is concerned.’” Other judges have chosen to remain. Civil unrest in Kazakhstan in January 2022, during which hundreds were killed, likewise raises questions about the future of the nation’s special economic zone (SEZ), and its bench of 100-percent English judges.

While many have noted the rise of international commercial courts, few have asked what social order they promote, “who would benefit from it,” and how it might “impact the interests and values of all affected people.”36 This research begins to address these questions. Traveling judges seem poised to promote a social order that continues the legacy of English common law empire and a coding of capital based in English (not New York) common law by instantiating it through the state sovereignty of certain small jurisdictions. This Article provides a jumping off point for a fuller contemplation of whom that social order will benefit and what role traveling judges will play in perpetuating or mitigating today’s global and globalized problems.

* Assistant Professor of Law, Queen’s University Faculty of Law.

** Associate Professor of Law, Fordham Law School. We thank the judges and court officials we interviewed, to whom we promised anonymity.

1. See Pamela K. Bookman & Alyssa S. King, Transnational Dispute Resolution, International Commercial Courts, and the Future of International Commercial Law, in Transnational Commercial Disputes in an Age of Anti-globalism and Pandemic (Sundaresh Menon & Anselmo Reyes eds., forthcoming 2022) (discussing international com- mercial courts’ potential to develop international commercial law in a manner that addresses global problems, and obstacles to their doing so).

2. See Standing International Forum of International Courts (SIFOCC), About Us, at https://sifocc.org/about-us.

3. Some of these jurisdictions are easy to learn about; others have a limited web presence, making research more challenging.

4. When using grounded theory, researchers start with a general research question and base their ultimate the- oretical contribution on patterns emerging from the data. Grounded theory is especially suited to the exploration of understudied phenomena. See Joshua Karton, The Culture of International Arbitration and the Evolution of Contract Law 30–37 (2013); Barney G. Glaser & Anselm L. Strauss, The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (1967).

5. SIFOCC members may include court systems, like the ECSC, individual courts, like the Southern District of New York, or commercial divisions like the New York Commercial Division, or whole judiciaries, like the Hong Kong SAR judiciary.

There may be additional commercially oriented courts with travelling judges, and even additional SIFOCC mem- bers, that should belong in this study, but we were unable to find sufficient information about them. See Part II infra.

6. Of the nine jurisdictions, only Kazakhstan was never under British influence. Today, Hong Kong, the DIFC, the QFC, the ADGM, and the AIFC are all common law jurisdictions located in non-common law countries.

7. The two courts are the AIFC courts in Kazakhstan and the ADGM courts in Abu Dhabi.

8. There are 235 seats on all these courts combined, eighty-one of which (34%) were occupied by seventy-two traveling judges (some sat on multiple courts). Some current traveling judges have also sat on other host courts in the past. For example, at least one judge on the SICC has previously served as a judge on the BVI Commercial Division in the ECSC.

9. The current U.S. judge on the SICC, a former Delaware Supreme Court justice, may soon step down, but a Del- aware Bankruptcy Court judge intends to join the court in 2022. Shermaine Ang, Senior Judge of the Supreme Court and 2 New International Judges Appointed for 2022, Straits Times (Nov. 16, 2021).

10. See, e.g., Anne-Marie Slaughter, A Global Community of Courts, 44 Harv. Int’l L.J. 191, 198 (2003).

11. SIFOCC lists three purposes of the organization: (1) to benefit court users, i.e., business and markets, by having courts share best practices; (2) to have courts work together to contribute to the rule of law, stability and prosperity; and (3) to support developing countries “to enhance their attractiveness to investors by offering effective means for resolving commercial disputes.” SIFOCC, supra note 2, at https://sifocc.org/about-us.

12. “The judiciary of the country becomes the member, rather than any individual judge.” Id.

13. SIFOCC, About Commercial, https://sifocc.org/about-us/#aboutcommercial.

14. See, e.g., Pamela K. Bookman, The Adjudication Business, 45 YALE J. INT’L L. 227, 230 n.13 (2020) (collecting sources). Examples of international commercial courts include the Paris International Commercial Chamber, the SICC, the Chinese International Commercial Courts, the DIFC courts, and the AIFC courts.

15. SIFOCC members include four U.S. courts (the SDNY, New York State Supreme Court Commercial Division, Supreme Court of Delaware, and Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas), the Business and Property Courts of En- gland & Wales (including the London Commercial Court), and the Supreme Courts of the Philippines, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Sri Lanka, and Uganda. SIFOCC also includes high courts in countries from South Korea to Nigeria.

16. Under a high court system, the high court (which may also be called a supreme or superior court) consists of a court of first instance and a court of appeal.

17. Of the forty-four members, ten courts (in Brazil, China, Bahrain, France (two), Germany, Japan, the Nether- lands, South Korea, and the UAE (Abu Dhabi Judicial Department)) can be described as civil law courts. Two are in mixed jurisdictions (the Philippines and Scotland). SIFOCC, Members (2022), at https://sifocc.org/countries.

18. As Anna Dziedzic has remarked, “the field of comparative law often assumes information is all available online and as such easily accessible,” but data collection on these courts is far from simple. Anna Dziedzic, Women Judges, Local Judges, Foreign Judges: Methods of Collecting and Analysing Data on Gender and Pacific Judiciaries, IACL-AIDC Blog (Nov. 9, 2021), at https://blog-iacl-aidc.org/women-judiciary/2021/11/9/women-judges-local-judges-for-eign-judges-methods-of-collecting-and-analysing-data-on-gender-and-pacific-judiciaries (remarking on collecting data on courts in Pacific Island states). The courts in our study vary tremendously in the availability of information about their structure and judges’ identities.

19. All data was double-coded.

20. For instance, the Hong Kong CFA and DIFC list current and former judges on their websites. Other courts do not. Some future information was available. For example, in 2021, the SICC announced that it would add a Delaware bankruptcy judge as well as a Japanese judge. Ang, supra note 9.

21. To conduct snowball sampling, researchers start with an initial list of interview subjects and then ask those subjects to recommend others who also know about the research subject. We began with initial contacts in several jurisdictions of interest. At the end of every interview, we asked the subjects to recommend colleagues who might speak with us. Frequently, participants were willing to make introductions by e-mail. The resulting sample of participants is neither randomized nor representative. However, this sort of sampling is appropriate when researchers want to understand a phenomenon involving a discrete social group. See Patrick Biernacki & Dan Waldorf, Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling, 10 Socio. Methods & Res. 141 (1981).

22. The SICC originally also had a judge from Japan and one from Austria.

23. Judges from mixed systems included those from Cyprus, Kuwait, South Africa, Malaysia, Scotland, and Can- ada. Cyprus and South Africa combine common law with French and Dutch influence. The Kuwaiti legal system also mixes common law, French civil law, and Islamic law. Malaysia, like several Middle Eastern jurisdictions, maintains a dual-track legal system with both common law and sharia courts. Being from a country with mixed legal traditions, however, does not guarantee much contact with different legal systems in practice. In Canada, for example, the sub- stantive law of the Canadian province of Quebec is civil law, but the two Canadian judges on our list are from the common law provinces of Ontario and British Columbia. Canadian Supreme Court justices have some exposure to Quebec law, but a common law justice would hardly be considered a civil law jurist. The Canadian Supreme Court maintains Quebec seats for this purpose.

24. See Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal Ordinance, 1997 (Cap. 484), § 12(4), at https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/ hk/cap484 (H.K.) ; West Indies Associated States Supreme Court Order 1967, Art. 18(1) (UK) (ECSC); Grand Court Law, 2015 Revisions, Art. 6(2), at http://gazettes.gov.ky/portal/pls/portal/docs/1/12022120.PDF (Cayman Is.). These jurisdictions all contemplate traveling judges on non-commercial courts.

25. These courts include the BVI commercial division, the Cayman Islands FSD, the Hong Kong CFA, the SICC, and the courts in the DIFC, QFC, ADGM, and AIFC. This list excludes the Supreme Court of The Gambia and the ECSC as a whole.

26. All English judges got their first law degrees in the UK. The eight Australian judges received their first law degrees in Australia, the two Canadians in Canada, and the two New Zealanders in New Zealand.

27. They are from Hong Kong (two), Bermuda (one), and Singapore (one). Although Jersey and Guernsey are separate jurisdictions and do not form part of the United Kingdom, we did not count judges from these jurisdictions as having gone “abroad.”

28. Interviews with J1 (July 12, 2021), J2 (July 23, 2021).

29. See, e.g., Interviews with J1 (July 12, 2021), J19 (Dec. 20, 2021).

30. See, e.g., Interview with J8 (Oct. 18, 2021) (one might become a traveling judge for “fun”).

31. Interview with J15 (Dec. 2, 2021).

32. Interviews with J2 (July 23, 2021); J3 (July 28, 2021); J7 (Oct. 11, 2021); J16 (Dec. 15, 2021).

33. Cf. Pamela K. Bookman, Arbitral Courts, 61 Va. J. Int’l L. 161 (2021) (suggesting that traveling judges make these courts resemble arbitration).

34. See Pamela K. Bookman, Traveling Judges Dealing in Virtue (draft on file).

35. Catherine Baksi, Hale Quits Hong Kong Judicial Post, L. Soc’y Gazette (June 4, 2021).

36. Thomas Schultz & Clément Bachmann, International Commercial Courts: Possible Problematic Social Externalities of a Dispute Resolution Product with Good Market Potential, in International Commercial Courts: The Future of Transnational Adjudication (Stavros Brekoulakis & Georgios Dimitropoulos eds., 2022), at 69 (rais- ing these questions).

37. See also, e.g., Bookman & King, supra note 1.