A Map for Progress on Fines and Fees

hortly before the pandemic, a judge in the Drug Court Part in Bronx Criminal Court tried to persuade a young man to enter a drug treatment program. However, the man said he couldn’t afford to stop working his job at a flooring company to address his substance abuse issues due to the huge fines and fees attached to his offenses hanging over his head. There was no leeway; due to a New York state law passed during the 1990s, the height of the “tough on crime” era, the judge could not waive the mandatory court fines and fees because of the young man’s inability to pay, nor as an incentive for the young man to complete treatment. As a result, the young man declined critical assistance.

In August 2019, Peggy Herrera, a mother from Queens, called emergency services when her 16-year-old son, who had been previously criminalized for his mental health issues, experienced an anxiety attack. After counseling, her son calmed down. The police, however, proceeded to remove her son from their home. Herrera, who had never been arrested, told the police she could assist her son herself. As she described in the New York Daily News, Herrera was tackled from behind and arrested. The following March, Herrera’s charges were dropped, but she and her family remain trapped in debt from mandated fines and fees.

“My son’s criminalization and my own arrest have caused not just emotional hardship for my family, but financial strain,” said Herrera, a community leader with the Center for Community Alternatives. “Our court fees and bail payments total more than $12,000, even though my son was a teenager and my case was dismissed.”

It’s not just New York. Nationwide, all 50 states and Washington, D.C., increasingly use the legal system to raise revenue from fines and fees whenever anyone has contact with the criminal justice system, whether the charge is a felony, a misdemeanor, a traffic ticket, or a minor municipal code violation. The purported purpose of fines, such as those charged for a speeding ticket, is deterrence. Fees, on the other hand, are purely revenue generators. In many states, fines and fees go directly into the coffers of courts or law enforcement. This creates a “perverse incentive” surrounding fines and fee-based revenue. For example, if fees pay salaries for law enforcement, police will have more incentive to make arrests and collect fees. These fines and fees result in a hidden, disproportionate tax on people who can least afford to pay, including Black and brown populations, those living in poverty, or those who are working class.

The National Center for Access to Justice (NCAJ), based at Fordham Law School, is working to reverse this trend. In 2021, NCAJ undertook a 50-state mapping and indexing analysis project, resulting in the Fines and Fees Justice Index, which ranks states based on their adoption of optimal practices for curbing excessive reliance on fines and fees.

The Fines and Fees Index measures the performance of each state against 17 benchmarks that NCAJ, working closely with an expert advisory group, identified as critical to creating a fairer system that does not criminalize poverty and respects the rights of litigants. These include, among others, abolishing all fees, abolishing juvenile court fines and fees, evaluating inability to pay fines and fees at sentencing and giving judges discretion to waive or modify costs accordingly, eliminating suspension of driver’s licenses and voting rights for failure to pay, and requiring proof of willful failure to pay before imposing incarceration and other sanctions.

This work is an extension of the NCAJ’s Justice Index, which was first released in 2014, updated in 2016, and then updated and expanded in 2021. The Justice Index is a data-intensive presentation of policy benchmarks against which states are measured to reveal their relative progress in increasing civil access to justice.

“Policy mapping and indexing are journalistic tools being rediscovered within law as a way of assuring that laws nationwide are sound,” said David Udell, executive director of NCAJ. “It’s routine to see news stories about where the environmental laws or hospital systems are better or worse, but it’s unusual to see states ranked based on their justice systems and policies, which is what we are tracking.”

The Fines and Fees Index shows, for example, that many states charge fees for court-appointed counsel in criminal cases. “We are able to show that the guarantee of a free lawyer under Gideon v. Wainwright doesn’t necessarily mean a court-appointed lawyer is really ‘free’ or provided without cost,” said Udell. “Many states charge a fee for the appointment of defense counsel. If you can’t pay at the time, the state will seek to collect it from you later, and it follows you for all your days.”

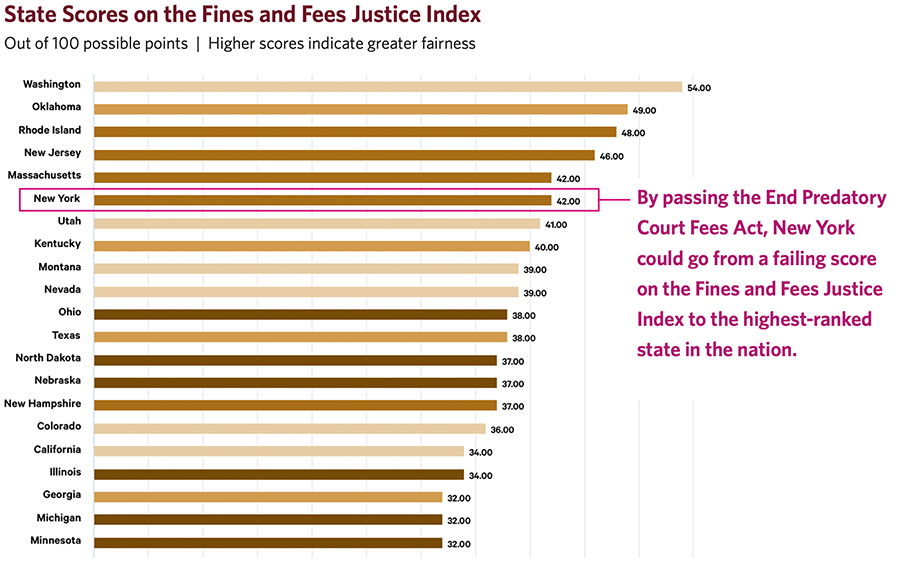

In a report released in May, “Increasing Justice in New York,” NCAJ analyzed how New York state could become the national model for decriminalizing poverty. By passing the End Predatory Court Fees Act, currently pending before the State Senate, New York could go from a failing score on the Fines and Fees Justice Index—42 out of a possible 100 points—to the highest-ranked state in the nation.

“In our Justice Index project, we find people in every state who are eager to use NCAJ’s research findings and state rankings to support local efforts to expand access to justice,” said Udell. “New York, NCAJ’s home, is no exception. Our new report shows how corrective legislation, currently pursued by advocates here in New York, would dramatically improve the state’s ranking in the Fines and Fees Justice Index.”

“The impact of outrageous and unjustified fines and fees crushes the ability of those coming out of the criminal justice system to reestablish their lives and become productive members of the community,” said Matthew Diller, Dean of Fordham Law School. “This is an opportunity for New York to become the leader in correcting this tremendous problem. NCAJ is a major voice in advocating for reform in this area. I am hopeful the report will have an impact.”

“Essentially, New York rolls many fees that other states charge into one sum to be paid upfront,” she added. In addition, people may owe hundreds or thousands of dollars in fines. Fines for felony convictions, for example, can reach $100,000.

“What’s been fascinating to us is that this is not a ‘red state vs. blue state’ problem,” said Jones. “It’s surprising, for example, that Oklahoma, which has a troublingly high rate of mass incarceration, is ranked near the top, with a 49 on the Fines and Fees Index. Oklahoma is the only state that has instituted day fines, which are tagged not just to the offense, but also to how much a person makes. This means the punishment—the fine—is felt more equally across incomes.”

Moreover, New York law does not allow for payment plans. While 2021’s Driver’s License Suspension Reform Act ended driver’s license suspensions for unpaid traffic tickets, that law does not apply to other types of violations. New York judges may still suspend driver’s licenses for failure to pay fines, fees, and surcharges associated with penal code violations, such as disorderly conduct or trespassing. Penalties for late payment can include incarceration, ruined credit, and ongoing debt. In another policy choice that reduced its score, New York also allows private debt collection agencies to collect fines and fees.

“James Baldwin once said, ‘Anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor,’” said Jones. “Fines and fees contribute to a two-tiered system of justice, where the penalties for an infraction for someone who is poor or working class are much harsher than those for people who have means. Millions of individuals can get trapped in years or lifelong cycles of punishment and poverty for having one infraction.”

Even minor traffic offenses come with a prohibitive fee. According to a study by the Vera Institute of Justice, the typical cost for driving with a suspended license in New York in 2018 was $633. For those with means, this cost may result in an inconvenience or a problem. For individuals who live in poverty or are working class, however, paying the fines and fees too often results in a Hobson’s choice of whether to pay these costs over the utility bill, credit card debt, or their next meal.

There is also a lack of transparency about how much revenue from fines and fees New York collects. Vera identified $1.21 billion collected from fines and fees in fiscal year 2018, divided among budgets of state government, cities, counties, towns, and villages. With the exception of a few small towns and villages with populations below 2,500 people, revenues from fines and fees accounted for less than 1% of those budgets. Almost all of the $665 million in fines and fees revenue in New York City in 2018 came from parking tickets, red-light cameras, and other traffic offenses. In states that have studied fines and fees revenue collection, states spend 40 cents for every dollar collected, more than 120 times what the IRS spends to collect taxes. “It’s a lot of money for individuals, but it’s not a huge revenue driver,” said Jones.

A better policy environment is within reach. According to NCAJ’s “Increasing Justice in New York” report, New York can become a model for fines and fees policies if it passes the End Predatory Court Fees Act. The proposed law would make New York the first in the nation to eliminate all criminal court surcharges and fees, as well as all probation and parole fees; abolish mandatory minimum fines and allow judges to set fines according to the ability to pay; require courts to assess a person’s inability to pay before imposing fines and allow people to apply for resentencing if they become unable to pay at a later date; end incarceration for failure to pay fines, fees, surcharges, and assessments; and end the practice of garnishing commissary funds from people who are incarcerated. (However, the legislation does not abolish fines and fees for civil and juvenile court.)

Moreover, other states, such as Alabama, Arizona, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, have introduced bills to curb or eliminate fines and fees. This is where NCAJ’s work has proven crucial: Because of the Fines and Fees Index, advocates both nationwide and in their respective states can see the benchmarks and compare their states to what other states are doing. With this added resource, they can point to the policies that are working and where the needs of vulnerable communities are being overlooked.